The Core Value and Industry Positioning of Prototype SMT Assembly

In today’s world of increasingly compressed electronic product development cycles, Prototype SMT Assembly is no longer just a simple step of “building a board and seeing if it lights up.” It’s a crucial link between design verification, engineering feasibility assessment, and mass production decisions. It directly impacts the project’s development pace, technical risk control, and the success rate of subsequent mass production.

Essentially, Prototype SMT Assembly is a manufacturing activity aimed at verification. Compared to mass production SMT, it focuses more on whether the design is manufacturable, whether the component selection is appropriate, whether the soldering process is stable, and the overall board’s performance under real-world operating conditions. The goal at this stage is not to pursue maximum efficiency or the lowest per-board cost, but to expose potential problems in the shortest possible time and in a manner as close to mass production conditions as possible.

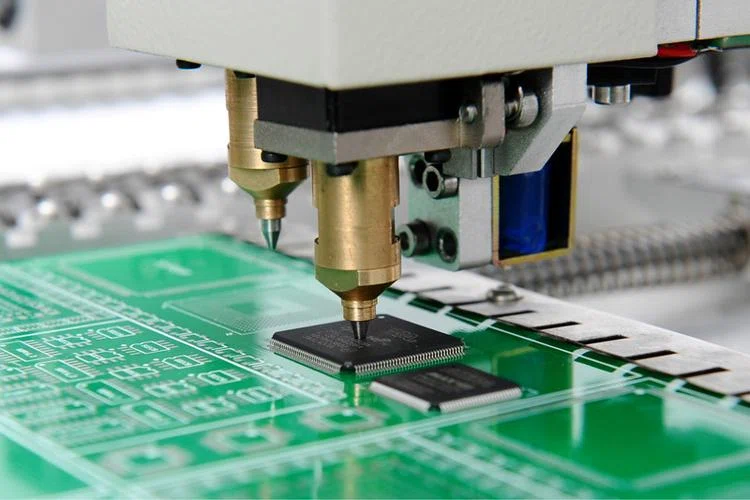

In real-world projects, many design flaws do not appear in the schematic or simulation stages but are truly “amplified” after the initial placement. For example, issues such as unreasonable pad design, mismatch between package selection and reflow process, bridging risks due to excessively small component spacing, and soldering defects caused by differences in thermal capacity can often only be accurately identified through Prototype SMT Assembly. This is why mature hardware teams often regard the prototype placement stage as an “engineering check-up.”

Unlike mass production SMT, which emphasizes consistency and scalability, Prototype SMT Assembly is characterized by high flexibility and engineering involvement. At this stage, the BOM may not be fully finalized, some components are still under evaluation for alternatives, and process parameters need to be dynamically adjusted according to the board structure. This requires SMT assembly not only to have equipment capabilities but also deep involvement of engineering experience; otherwise, prototype results can easily deviate from actual mass production performance, misleading subsequent decisions.

From a market perspective, the value of Prototype SMT Assembly is constantly increasing. As product complexity increases and component packaging becomes increasingly sophisticated, high-speed, high-density designs have become the norm. If a judgment is made incorrectly during the prototype stage, the cost of subsequent modifications will be multiplied. In comparison, investing more engineering resources in placement verification during the prototype stage is a more cost-effective choice. Therefore, Prototype SMT Assembly should not be viewed as a “transitional step before mass production,” but rather as a concentrated manifestation of product engineering capabilities. It not only verifies whether the design is “feasible,” but also whether it is “worth entering mass production.” The quality of this stage often determines the smoothness of the entire project’s later stages.

The Fundamental Difference Between Prototype SMT Assembly and Mass Production SMT

In actual projects, a common but dangerous misconception is understanding Prototype SMT Assembly using the logic of mass production SMT. Superficially, the equipment, soldering processes, and even material systems used are highly similar, but in terms of goals, decision-making methods, and engineering focus, they essentially serve completely different stages.

The core goals of mass production SMT are stability, efficiency, and consistency. Once process parameters are confirmed, frequent adjustments are avoided as much as possible to ensure yield and cost control for large-volume products. The primary goal of Prototype SMT Assembly is not “stable output,” but rather proactively exposing unstable factors. This stage is more like a controlled experiment, verifying whether the design and process truly match through a limited number of prototypes.

In prototype SMT, the BOM and design are often still in a dynamic state. Some key components may have multiple package or brand options, and the pad design may not have yet undergone mass production verification. This means that prototype SMT assembly is not just about “performing placement,” but also about providing a basis for decision-making in subsequent mass production. If problems are deliberately concealed at this stage in pursuit of surface finish, it will amplify risks in the mass production stage.

The difference in process strategies is equally significant. Mass production SMT typically uses standardized reflow profiles and mature process windows to adapt to the vast majority of products; while in prototype SMT assembly, engineers often need to perform targeted optimizations for a single board type. High copper thickness, multilayer boards, mixed components, or large-size packages can all significantly impact local solder quality. Only by actively adjusting and recording these differences during the prototype stage can reliable references be provided for mass production.

Another key difference lies in the way problems are handled. In the mass production stage, anomalies are often seen as fluctuations that need to be suppressed quickly; while in prototype SMT assembly, anomalies are precisely the most valuable source of information. Poor soldering, component misalignment, localized cold solder joints, or uneven reflow do not necessarily indicate failure; rather, they provide direct evidence for design modifications and process optimization.

From an engineering management perspective, Prototype SMT Assembly emphasizes cross-departmental collaboration. Design, process, procurement, and manufacturing teams need to maintain frequent communication at this stage; otherwise, prototype results can easily be interpreted in isolation, losing their true value. In contrast, mass production SMT relies more on established processes and procedures, and is less dependent on immediate decision-making.

Because of these fundamental differences, the success standard for Prototype SMT Assembly should not be simply equated with “the prototype working.” It should measure whether conflicts between design and manufacturing have been identified in advance, and whether clear and actionable improvement directions have been provided for mass production. Only by understanding the role of prototype SMT at this level can the common pitfall of “successful prototype, failed mass production” be avoided.

The Most Easily Overlooked Engineering Risks in Prototype SMT Assembly

In the Prototype SMT Assembly stage, the real danger is not obviously failed prototypes, but rather those results that “appear to be fine”. Having a board that powers on and functions normally doesn’t mean the design and process are ready for mass production. On the contrary, many risks affecting mass production yield and long-term reliability are unintentionally overlooked during the prototype stage.

First, the underestimation of the potential for problems stems from the limited number of prototypes. Prototype SMT assembly often involves only a small number of boards, allowing chance-based process fluctuations to be masked by “luck.” For example, some pad designs may have extremely narrow wetting windows, which might fall within an acceptable range in a prototype, but once mass production begins, even minor material or temperature fluctuations can rapidly reduce yield. If the prototype stage focuses only on functional verification without statistically assessing process robustness, mass production risks are almost inevitable.

Second, there’s the distortion caused by human intervention. In prototype placement, engineers and operators often invest more effort in manually reworking abnormal solder joints, fine-tuning parameters, and even making temporary compromises. This “engineering compensation” may seem reasonable during the verification phase, but it masks the true manufacturing difficulties. Once mass production begins and this intensive human intervention is lost, problems will erupt all at once. Therefore, if a prototype fails to pass near-mass production conditions naturally, it should be considered a warning sign.

The third common risk stems from uncertainties in components and the supply chain. The components used in prototype SMT assemblies are often not the final mass-production versions, but may come from different batches or temporary replacement models. This may not immediately manifest in functionality, but significant variations can occur in soldering windows, thermal characteristics, and reliability. If prototype verification does not simultaneously assess component availability and batch consistency, new soldering problems are highly likely to arise during subsequent mass production switchovers.

Furthermore, it is very common for reflow soldering profiles to be “just usable” in the prototype stage. Engineers may achieve soldering success on the prototype board through meticulous adjustments, but this profile has extremely low tolerance for environmental changes, board thickness variations, or equipment differences. Once replicated to different production lines or equipment, consistent soldering quality becomes difficult to maintain. These risks are often inconspicuous in the prototype stage but are significant contributing factors to mass production failures.

Finally, passing functional testing does not equate to reliable performance. The prototype SMT assembly phase typically focuses on lighting, communication, or basic performance verification, but rarely includes stress testing or long-term operational verification. This makes it difficult to promptly expose issues such as cold solder joints, microcracks, or insufficient edge wetting, which are precisely the main sources of rework and field failures after mass production.

Therefore, the real challenge of prototype SMT assembly is not “whether it can be done,” but rather the ability to identify problems that will be amplified by economies of scale within a limited prototype. Ignoring these engineering risks often means postponing uncertainty to the more costly and impactful mass production stage.

How to Effectively Reduce Mass Production Failure Rate Through Prototype SMT Assembly

The true value of prototype SMT assembly lies not in whether the prototype is successfully completed, but in whether it establishes a clear and replicable engineering foundation for the mass production stage. If the prototype phase is merely an isolated success story without accumulating executable experience, then deviations after entering mass production are almost inevitable.

First, prototype SMT should be viewed as a scaled-down rehearsal before mass production. Where conditions permit, placement equipment, reflow ovens, solder paste types, and operating procedures should be as close as possible to the mass production state. The purpose of this is not to pursue a perfect appearance, but to verify the adaptability of the existing design in a real manufacturing environment. If a prototype can only pass with specific parameters or high manual intervention, it indicates insufficient mass production robustness of the design.

Secondly, the Prototype SMT Assembly stage should focus on the process window rather than single-point results. Instead of pursuing a qualified prototype under a certain set of parameters, it’s more effective to systematically evaluate the sensitivity of soldering quality to temperature, time, and material fluctuations. Comparative analysis of solder joint conditions in different areas can determine whether the current design has sufficient process tolerance, providing a basis for setting mass production curves.

Thirdly, Design Manufacturability (DFM) feedback should be conducted concurrently during the prototype stage. Many soldering problems are not due to equipment or operational errors, but rather stem from unreasonable pad design, component spacing, or layout logic itself. The actual soldering performance obtained through Prototype SMT Assembly is the most direct data source for verifying DFM assumptions. Reflecting this feedback in design modifications in a timely manner is often more effective than adjusting process parameters later.

Furthermore, prototype SMT should also serve as a supply chain validation tool. Preliminary assessments of the packaging consistency, soldering performance, and substitutability of key components can effectively reduce process risks caused by component changes during mass production. This step is particularly valuable in the current environment of significant supply chain volatility.

Finally, the conclusions of the prototype phase must be systematically recorded and communicated. Reflow curves, anomalies, rework locations, and engineering judgment criteria are all crucial references for mass production initiation. If this information remains at the level of personal experience, the mass production phase can easily repeat past mistakes due to changes in personnel or equipment.

Overall, the core goal of the Prototype SMT Assembly is not simply “making a good prototype,” but rather preemptively mitigating the uncertainties of mass production. It truly fulfills its mission when the prototype phase can clearly answer questions such as “Where are the risks, where do they come from, and how can they be controlled?”

Conclusion

Prototype SMT Assembly: The True Starting Point for Mass Production Success

In summary, the Prototype SMT Assembly is not merely a formality before mass production, but a critical engineering phase that determines the success or failure of the project. It encompasses more than just placement and soldering verification; it’s a comprehensive test of design rationality, process robustness, and supply chain feasibility.

During the prototype stage, the cost of identifying problems is lowest, and the scope for engineering adjustments is greatest. If these potential risks are ignored or postponed to mass production, it will not only directly impact yield and delivery time but may also lead to a chain reaction of consequences such as repeated rework, customer complaints, and even project failure. Therefore, truly mature teams treat Prototype SMT Assembly as a “magnifying glass” of engineering verification, rather than a simple functional confirmation.

By systematically evaluating process windows, DFM issues, device consistency, and manufacturing stability during the prototype SMT stage, uncertainties can be mitigated as early as possible, establishing a clear and replicable execution foundation for mass production. This upfront investment is often the most effective way to reduce overall costs and improve product reliability.

In other words, the success or failure of mass production is often determined during the Prototype SMT Assembly stage.