PCB loop area refers to the physical spatial area enclosed by the closed circuit formed by current flow on a printed circuit board (PCB). It is a critical factor influencing a circuit’s electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) and signal integrity. Loop area serves as a pivotal metric for determining signal integrity (SI) and electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) in 4 layer boards. Excessive loop sizes not only exacerbate signal attenuation, reflections, and crosstalk but also heighten electromagnetic radiation and susceptibility. Unlike double-layer boards which rely on surface-layer routing to barely control loops, the inner layers of a 4 layer board (typically ground and power planes) possess inherent reference plane advantages. Through scientific stackup planning and inner-layer utilisation strategies, loop area can be significantly reduced, providing stable transmission assurance for high-speed, high-frequency circuits.

Relationship between inner layers and loop area in 4 layer boards

The essence of loop area lies in the enclosed region formed by signal transmission paths and return paths. Longer paths and greater spacing increase loop area, leading to heightened signal loss and electromagnetic interference. A typical 4 layer board stackup structure is “Top layer (signal layer) – Inner layer 1 (ground plane) – Inner layer 2 (power plane) – bottom layer (signal plane)”, though in high-interference scenarios both inner layers may be configured as ground planes. The core value of these inner layers lies in providing continuous, low-impedance reference planes. This allows return paths to closely follow signal transmission paths, minimising return distances at source and thereby reducing loop area.

Unlike double-layer boards lacking dedicated reference planes where return paths are forced to detour, the inner layers of a 4 layer board function as specialised reference planes. This enables a synergistic mode where ‘signals traverse the outer/inner layers while return paths utilise the adjacent inner layer reference plane’. The greater the continuity of the copper cladding on the inner reference plane and the closer its proximity to the signal layer, the lower the impedance of the return path. This significantly reduces the divergence of return paths, thereby controlling loop area to the minimum extent. Practical data indicates that, at identical signal rates, optimised 4 layer boards utilising inner layers can reduce loop area by over 60% compared to traditional double-layer boards, while lowering electromagnetic radiation intensity by 40%-50%. This fully satisfies transmission requirements for mainstream high-speed signals (1-5GHz).

Notably, the reference plane attributes of inner layers in 4 layer boards are not fixed; ground and power planes can flexibly switch roles according to signal demands. In scenarios where analogue and digital signals coexist, the inner ground plane can serve as an isolation reference plane. This provides independent return paths for both signal types while preventing loop cross-over and superposition. For high-power supply scenarios, the inner power plane can collaborate with the ground plane to form a low-impedance power supply loop. Simultaneously, it provides a stable reference for surface-layer signals, achieving dual loop optimisation for both power delivery and signal transmission.

Strategies for Reducing Loop Area Using Inner Layers

1.Laminate Structure Optimisation

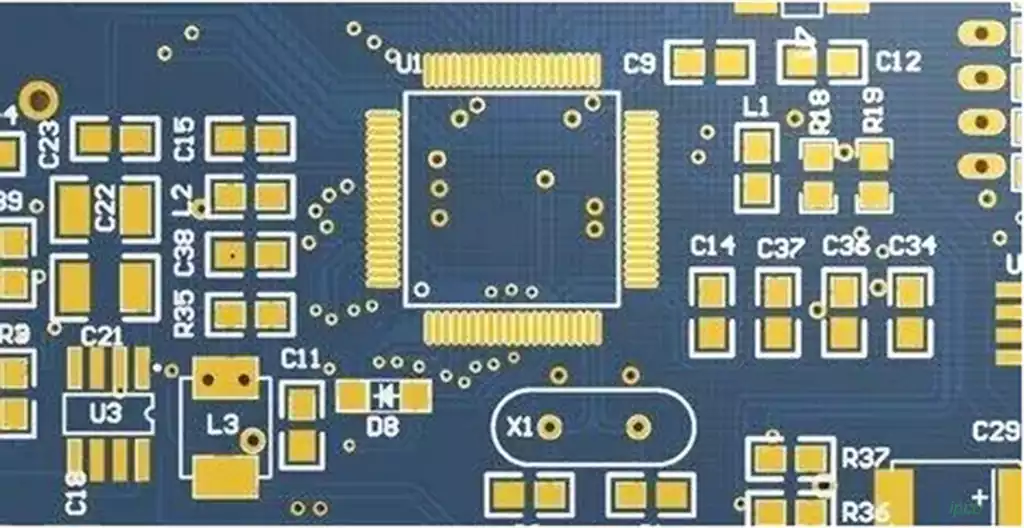

Laminate design forms the foundation for inner layer utilisation, directly determining the upper limit of loop area optimisation. To minimise loop area, a 4 layer board laminate must adhere to the core principles of ‘signal layers adjacent to reference planes’ and ‘continuous reference planes without segmentation’. Two primary optimisation approaches should be prioritised: The first is the classic ‘signal-ground-power-signal’ stackup, suitable for most general-purpose electronic devices. Signals are routed on the top and bottom layers, with inner layer 1 as a complete ground plane and inner layer 2 as a complete power plane. Signal return paths directly traverse the adjacent ground/power planes, minimising loop area to the tiny region defined by signal width and layer spacing. The second is the reinforced ‘Signal-Ground-Ground-Signal’ stackup, suitable for high-frequency, high-interference scenarios (e.g., RF modules, industrial control circuits). Both inner layers function as ground planes, forming a dual reference plane. This not only further shortens return paths but also enhances electromagnetic shielding, preventing external interference from affecting loop stability.

Two common pitfalls must be avoided during stack-up optimisation: firstly, arbitrarily segmenting inner layer reference planes to maximise routing space forces return paths to detour, drastically increasing loop area; secondly, increasing the spacing between signal layers and inner reference planes may reduce material costs but diminishes coupling effectiveness, elevates return impedance, and indirectly enlarges loop area. In practice, maintain a 0.2–0.4mm spacing between signal layers and inner-layer reference planes, employing 1oz–2oz copper thickness for inner layers to ensure low-impedance characteristics and efficient coupling.

2.Refined Design of Inner Layer Reference Planes

Maintaining continuity of inner layer reference planes is crucial for controlling loop area. Even minor divisions or gaps can cause return paths to detour, leading to exponential increases in loop area. For the two core inner layers—ground planes and power planes—differentiated, refined design strategies are required:

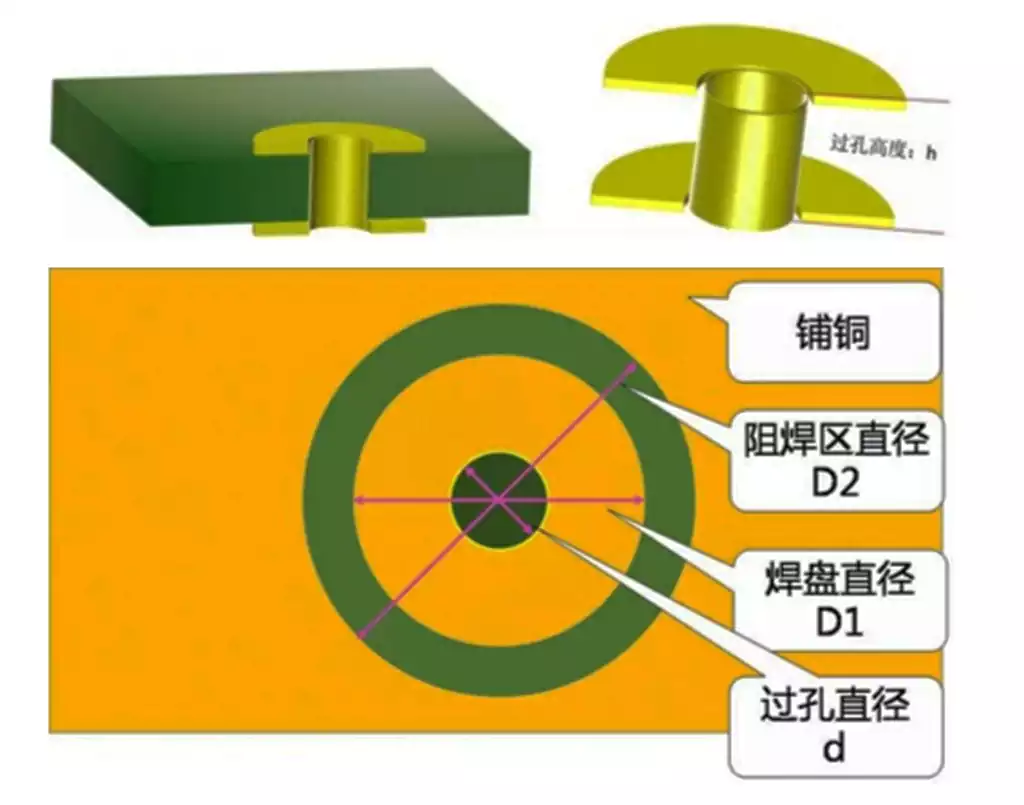

For inner ground planes, maintain overall continuity, introducing localised segmentation only when necessary (e.g., for power partition isolation). Segmentation lines must be perpendicular to signal propagation directions, with densely placed ground vias at segmentation points to achieve low-impedance connections between partitioned ground planes, providing the shortest return paths for cross-partition signals. For instance, when top-layer signals traverse from digital to analogue zones, ground vias at partition points enable return currents to switch reference planes directly through the via, preventing large loops formed by detours along partition lines. Furthermore, reverse pads should be judiciously designed at locations corresponding to surface vias and device pins on the ground plane. This prevents short circuits between vias and the ground plane while minimising reverse pad area to avoid disrupting reference plane continuity. The reverse pad diameter is recommended to be 0.2-0.3mm larger than the via diameter, balancing insulation requirements with plane integrity.

For inner-layer power planes, employ a ‘grid-pattern via’ design. Densely arrange power and ground vias between the power and ground planes to form low-impedance power supply loops. Simultaneously, these vias can serve as auxiliary return paths for surface-layer signals, further shortening return paths. In multi-voltage domain scenarios, power plane segmentation must correspond to ground plane segmentation, establishing a ‘one-to-one’ voltage-ground reference pair. This prevents cross-interference between return paths of different voltage domains while controlling loop area per voltage domain to avoid cumulative effects.

3.Co-design of Via Holes and Inner Layers

Via holes serve as the core components for cross-layer connections in 4 layer boards, yet they represent nodes where loop area can easily spiral out of control. Improper via hole design may disrupt return paths, forcing detours that subsequently expand loop area. Optimising via nodes through inner layer design requires focusing on three key dimensions:

Firstly, pairing vias with inner layer reference planes: assign 1-2 adjacent ground vias to each surface layer signal via, maintaining a spacing of less than 3mm between signal and ground vias to form a ‘signal-ground’ pairing structure. When signals traverse viaholes from top to bottom layers, return currents can flow directly through ground viaholes from the inner ground plane, avoiding large loops caused by surface-layer detours. For high-speed signal viaholes, ground viahole counts should scale with signal frequency: above 3GHz, two ground viaholes per signal viahole are recommended to further reduce return impedance.

Secondly, prioritise blind/buried vias over through-holes. Through-holes traversing the entire 4 layer board simultaneously penetrate both inner ground planes and power planes. Improper handling may disrupt reference plane continuity while increasing via length and parasitic parameters, indirectly compromising loop stability. Blind/buried vias traverse only designated layers (e.g., blind vias connect the top layer to inner ground planes, buried vias connect inner ground planes to power planes). This minimises impact on unrelated inner layers while shortening via length, reducing parasitic inductance and capacitance, concentrating return paths, and simplifying loop area control. In practice, employ blind/buried vias exclusively for signals spanning only two layers. For signals necessitating four-layer traversal, densely arrange ground vias around through-holes to enhance the return capability of the inner layer reference plane.

Thirdly, control via density and distribution. On high-speed signal paths, strictly limit via count—no more than two per signal trace—to prevent cumulative via effects from amplifying loop area. In densely populated via areas (e.g., component pin pads), synchronously increase ground via density to create localised low-impedance return paths. This prevents mutual interference and expansion of return paths from multiple vias.

4.Coordinated Management of Top Layer Routing and Inner Layers

The rationality of top-layer signal routing directly determines the optimisation effectiveness of inner-layer reference planes. Only through coordinated management can loop area minimisation be achieved. Routing must adhere to three principles: coplanarity with inner layer reference planes, shortest path, and avoidance of layer-to-layer traversal. Surface layer signal routing should run parallel to the copper texture of inner layer reference planes to enhance coupling and shorten return paths. Transmit and receive points for the same signal should be placed on the same surface layer whenever possible, minimising the number of cross-layer vias and preventing return paths from traversing layers. Where cross-layer routing is unavoidable, ensure corresponding inner-layer reference planes and ground vias exist near the vias to form complete return paths.

Additionally, control trace width and spacing on the top layer. Trace width should be adjusted based on signal rate and current requirements (0.2-0.3mm recommended for high-speed signals), while spacing adheres to the ‘3W principle’ (spacing ≥ 3 times trace width) to prevent loop interference from adjacent signals. For differential signals, maintain equal trace lengths and uniform spacing between the two signal lines. Ensure the differential pair exhibits symmetrical coupling with the inner layer reference plane to balance return paths, thereby further reducing differential loop area and mitigating common-mode interference.

Techniques for Balancing Inner Layer Optimisation with Cost and Process Feasibility

When utilising inner layers to reduce loop area, it is essential to balance performance, process feasibility, and cost to avoid excessive optimisation driving up manufacturing expenses. In mass production scenarios, three key trade-offs warrant attention: Firstly, the selection between blind/buried vias and through-holes. Whilst blind/buried vias offer significant optimisation, their manufacturing complexity incurs a 30%-50% higher cost than through-holes. Consequently, through-holes should be prioritised for non-high-speed signals, reserving blind/buried vias solely for core high-speed signals (e.g., USB 3.0, PCIe). Secondly, balancing inner layer copper thickness against cost. 1oz copper typically suffices for ground plane requirements in most scenarios. While 2oz copper reduces impedance, it increases board weight and cost, making it suitable only for high-power, high-interference applications. Thirdly, balancing ground plane segmentation with routing. If inner layer segmentation is necessary, signal paths must be pre-planned to prevent routing difficulties post-segmentation, which could force longer signal paths and increased loop areas.

Concurrently, design solutions must be adapted to align with PCB manufacturing capabilities. For instance, certain manufacturers possess limited precision in blind/buried via processing, necessitating prior confirmation of minimum via diameter and spacing to prevent designs exceeding process limits. Inner layer reverse pads and via placement must account for etching process tolerances, reserving approximately 0.1mm tolerance to prevent short circuits or open circuits during mass production, thereby ensuring the integrity of the inner layer reference plane and the stability of loop optimisation effects.

Methods for Evaluating Loop Area Reduction Following Inner Layer Optimisation

After implementing inner layer optimisation solutions, professional verification methods must be employed to confirm loop area reduction and ensure compliance with design requirements. Common evaluation approaches comprise three categories: Firstly, simulation validation utilises tools such as HyperLynx or Ansys SIwave to construct 4 layer board 3D models. This simulates the synergistic effects of inner layer reference planes, vias, and routing. Performance enhancements post-optimisation are quantified through loop area simulation, S-parameter analysis (insertion loss, return loss), and EMC radiation simulation. Secondly, physical testing: after prototyping, measuring signal impedance continuity with a network analyser and assessing radiation intensity via EMC test equipment. Comparing pre- and post-optimisation data verifies the loop area reduction’s impact on SI and EMC improvements. Thirdly, process validation: inspecting the continuity of inner-layer reference planes and the reliability of via connections to inner layers, preventing process defects from nullifying optimisation gains.

4 layer board inner layer optimisation requires balancing performance gains with cost and manufacturing constraints. Through scientific design, collaborative management, and rigorous validation, loop area can be effectively reduced, providing reliable assurance for stable operation of high-speed circuits.