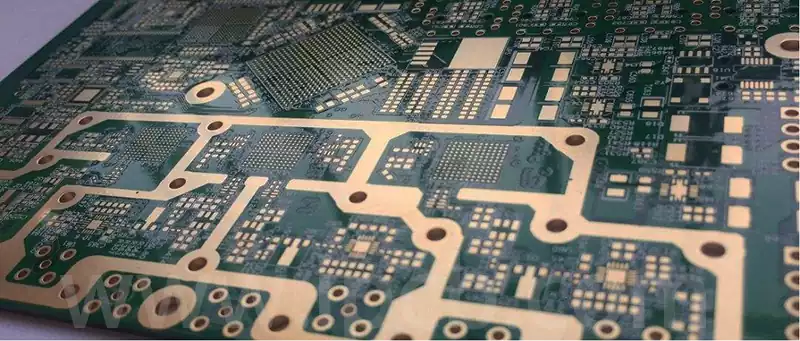

Below is a faithful, technically accurate, and idiomatic English translation suitable for professional use in electronics manufacturing, PCB engineering, or technical marketing materials.As the mainstream PCB substrate, the performance stability of FR4 directly determines the reliability of end products. However, during the drilling process, the high-speed penetration of the drill bit into the substrate generates mechanical impact, frictional heat, and cutting stress, which can cause latent damage within FR4, such as burrs, microcracks, and delamination. These defects are difficult to detect at an early stage, yet under extreme operating conditions—such as high temperature or vibration—they may trigger short circuits, open circuits, or structural failure. Therefore, analyzing the damage mechanisms induced by drilling and establishing a systematic prevention and control framework are critical for electronics manufacturers to improve PCB yield and reduce rework costs.

Three Primary Modes of FR4 Damage Induced by Drilling

1.Mechanical Damage

Mechanical damage is the most direct form of drilling-induced degradation in FR4, primarily resulting from the cutting force and impact generated by the rotating drill bit. It typically manifests as three major defects: hole-wall burrs, entry/exit edge chipping, and internal microcracks.

Hole-wall burrs are the most common surface defect, particularly at the interfaces between glass fibers and resin in FR4. When the drill bit cuts through glass fibers, insufficient edge sharpness or improper cutting speed may prevent clean shearing, resulting in filamentary or flaky burrs measuring approximately 0.1–0.5 mm in length. If not completely removed, these burrs can compromise adhesion between the hole wall and subsequent plating layers, or even pierce the insulating layer and cause short circuits between adjacent traces. Entry and exit edge chipping typically occurs on the top and bottom surfaces of the FR4 laminate and is caused by the impact force at the moment of drill entry and breakthrough exceeding the material’s edge strength. This leads to tearing of the glass fabric and resin detachment, forming irregular notches with diameters of 0.2–1 mm, which severely affect both mechanical integrity and cosmetic quality.

Compared with visible burrs and chipping, internal microcracks are more concealed and far more hazardous. During drilling, radial pressure from the drill bit induces plastic deformation in the FR4 material surrounding the hole. When the stress exceeds the bonding strength between the epoxy resin and glass fibers, microscopic cracks (typically less than 0.01 mm in width) form within the laminate. These microcracks can propagate during subsequent soldering or aging processes, ultimately leading to delamination, reduced mechanical strength, or even hole-wall fracture. Experimental data indicate that FR4 laminates containing internal microcracks exhibit a 30–50% reduction in flexural strength and a service life reduction of over 60% under high-temperature conditions.

2.Thermal Damage

During high-speed drilling, intense friction between the drill bit and FR4 generates substantial heat, causing localized hole-wall temperatures to rise rapidly—often reaching 200–300°C—far exceeding the glass transition temperature (Tg = 130–140°C) of standard FR4. Such elevated temperatures directly induce thermal degradation and oxidation of the resin, resulting in a series of performance deteriorations.

When temperatures exceed Tg, the epoxy resin transitions from a rigid glassy state to a rubbery state, significantly reducing bonding strength and causing localized separation between the resin and glass fabric around the hole wall, thereby creating latent delamination risks. If temperatures rise above 250°C, the epoxy resin undergoes thermal decomposition, releasing low-molecular-weight gases such as carbon dioxide and water vapor. Accumulation of these gases within the laminate forms microvoids, compromising material density and structural integrity. Additionally, high temperatures degrade the dielectric properties of FR4, increasing dielectric loss (Df) and adversely affecting signal integrity in high-frequency applications.

Thermal damage is inherently latent. Although drilled FR4 surfaces may show no immediate abnormalities, resin degradation has already undermined long-term stability. During actual product operation, repeated thermal cycling gradually reveals delamination and cracking in thermally damaged regions, significantly shortening product lifespan.

3.Resin–Fiber Interface Degradation

The mechanical strength and insulation performance of FR4 depend on the robust bonding between epoxy resin and glass fiber fabric. The combined mechanical and thermal stresses generated during drilling directly compromise this interface, leading to fundamental material failure.

Mechanically, cutting forces induce tensile and shear deformation in the glass fibers. When the epoxy resin cannot accommodate these stresses synchronously, microgaps form at the interface. Thermally, the mismatch in coefficients of thermal expansion (CTE)—approximately 60–80 ppm/°C for epoxy resin versus 5–10 ppm/°C for glass fiber—causes uneven thermal expansion and contraction under localized high temperatures, further widening interfacial gaps. These defects undermine the structural integrity of FR4, significantly reducing impact resistance and flexural strength, while also lowering insulation resistance and increasing leakage risk.

In severe cases, interface degradation leads directly to delamination, where the glass fabric fully separates from the epoxy resin in the drilled region, forming visible interlayer voids. Delaminated FR4 cannot withstand subsequent soldering temperatures or mechanical stress, resulting in immediate PCB scrap.

Four Key Factors Influencing the Severity of Drilling-Induced Damage

1.Drill Bit Parameters

Drill bit design and material directly determine cutting force and friction, making them the most critical factors affecting FR4 damage. Parameters such as point angle, edge sharpness, diameter, and material selection are particularly influential.

For FR4, the optimal point angle is 130°–140°. Smaller angles (90°–110°) generate excessive axial force, increasing the likelihood of edge chipping and internal cracking, while larger angles (150°–160°) raise cutting resistance and frictional heat, exacerbating thermal damage and burr formation. Edge sharpness is equally critical: sharp edges enable clean cutting of fibers and resin, minimizing mechanical stress, whereas dulled edges cause compression and tearing, significantly increasing burrs and microcracks. Drill diameter must also be matched to laminate thickness; when the diameter is below 0.8 mm and FR4 thickness exceeds 2 mm, drill deflection is more likely, leading to uneven hole-wall stress and localized damage.

In terms of material, carbide drill bits (e.g., tungsten–cobalt alloys) outperform high-speed steel due to superior hardness and wear resistance, maintaining edge sharpness longer and reducing mechanical damage. Their higher thermal conductivity also facilitates heat dissipation, lowering the risk of thermal damage.

2.Process Parameters

Drilling process parameters—spindle speed, feed rate, and cooling method—directly influence cutting force and heat generation and are therefore key levers for damage control.

The balance between spindle speed and feed rate is critical. Low spindle speed increases cutting force, promoting burrs and chipping, while excessive speed dramatically increases frictional heat and thermal damage. For standard FR4 (1.6 mm thickness) drilled with a 0.8 mm bit, the optimal spindle speed is 20,000–30,000 rpm with a feed rate of 0.1–0.2 mm/rev. Excessive feed rates increase instantaneous cutting volume and stress beyond material limits, causing cracks and delamination; overly slow feed rates prolong tool–material contact, allowing heat accumulation and worsening thermal damage.

Cooling effectiveness is particularly significant. Without cooling, hole-wall temperatures can exceed 250°C. Compressed air cooling can reduce temperatures to approximately 180°C, while dedicated cutting oil can maintain temperatures below 120°C, effectively preventing thermal damage. Cooling media also remove chips, reducing secondary abrasion of the hole wall.

3.Intrinsic FR4 Material Properties

Different FR4 grades exhibit significant variation in resistance to drilling-induced damage, primarily due to resin formulation, glass fabric specification, and lamination process.

High-Tg FR4 (Tg ≥ 170°C), formulated with modified epoxy resin, offers superior heat resistance and bonding strength, making it more resistant to thermal damage and interfacial failure than standard FR4. FR4 enhanced with toughening agents provides improved impact resistance and reduced microcrack formation. Glass fabric specification also matters: high-count fabrics (e.g., 7628) feature higher fiber density and stronger resin bonding, offering better resistance to cutting damage, whereas thinner fabrics are more prone to chipping and tearing.

Lamination parameters further influence damage resistance. Insufficient temperature or pressure results in weak resin–fiber bonding and increased delamination risk during drilling, while excessive lamination introduces residual stress that can be released during drilling, exacerbating microcrack formation.

4.Equipment Precision

Drilling equipment precision—including spindle runout, positioning accuracy, and Z-axis feed control—directly affects process stability. Insufficient precision leads to drill deflection and uneven stress distribution, intensifying FR4 damage.

Spindle runout exceeding 0.01 mm causes radial oscillation, leading to localized overcutting, burrs, and microcracks. Poor positioning accuracy results in misaligned entry angles, increasing edge chipping. Inadequate Z-axis feed accuracy causes feed-rate fluctuations, destabilizing cutting forces and increasing both mechanical and thermal damage. Vibration control is equally critical, as excessive vibration induces high-frequency impact between the drill bit and substrate, accelerating internal crack formation.

Core Strategies to Minimize Drilling Damage to FR4

1.Optimized Drill Bit Selection

Selecting drill bits precisely matched to FR4 properties and drilling requirements is fundamental. For standard FR4 (≤2 mm thick), carbide drill bits with 130°–140° point angles and precision-ground sharp edges are recommended. For high-Tg or thick FR4 (>2 mm), chamfered-point drills help reduce entry impact. For small-diameter holes (<0.6 mm), fine-shank carbide drills improve rotational stability.

A structured tool-life management system should be implemented. Carbide drill bits typically have a service life of 500–800 holes; tools should be replaced upon reaching this threshold to prevent damage caused by edge wear. Pre-use inspection is essential to ensure spindle runout ≤0.01 mm and to eliminate deformed or worn tools.

2.Precise Process Parameter Control

Process parameters should be optimized experimentally based on FR4 grade and hole specifications to balance efficiency and damage control. For standard FR4 (1.6 mm thick, 0.8 mm hole), recommended parameters are 25,000 rpm spindle speed, 0.15 mm/rev feed rate, and oil-based cooling. For high-Tg FR4, spindle speed may be increased to 30,000 rpm with feed rate reduced to 0.12 mm/rev to mitigate thermal damage. For thick FR4 (3.2 mm, 1.0 mm hole), a step-drilling process—first drilling to 1.6 mm depth, then completing the hole—reduces stress and heat accumulation.

Drilling sequence should also be optimized: drill smaller holes before larger ones, and edge holes before central holes, to minimize uneven stress distribution. Regular chip removal from the drill and worktable is essential to prevent secondary abrasion.

3.Enhanced Substrate Quality

FR4 selection should align with application requirements. For high-frequency or high-temperature applications, high-Tg (≥170°C) FR4 with high bonding strength is preferred. For thick PCBs, FR4 reinforced with high-count glass fabric (e.g., 7628) improves mechanical strength. For mission-critical applications such as automotive electronics or medical devices, toughened FR4 grades should be used to minimize microcrack formation.

Incoming material inspection should focus on resin content, bonding strength, and moisture content. Recommended specifications include resin content of 45–55%, bonding strength ≥1.5 N/mm, and moisture content ≤0.2%. Materials exceeding moisture limits should undergo pre-baking (120°C for 2–4 hours) to prevent delamination and void formation caused by moisture vaporization during drilling.

4.Ensuring Equipment Precision

Regular maintenance and calibration of drilling equipment are essential. Daily startup checks should verify spindle runout, positioning accuracy, and Z-axis feed accuracy, ensuring runout ≤0.01 mm, positioning accuracy ≤0.02 mm, and Z-axis accuracy ≤0.01 mm. Weekly lubrication of guides and lead screws reduces friction-induced vibration, while monthly inspection of spindle motors and servo systems ensures stable operation.

Workholding should be optimized using combined vacuum suction and mechanical clamping to minimize vibration and substrate movement. For thin FR4 (<0.8 mm), dedicated backing boards (e.g., phenolic resin boards) should be used to reduce entry and exit edge chipping.

5.Strengthened Inspection and Control

A full-process inspection system is necessary to detect both visible and latent drilling damage. Surface inspection should employ high-magnification microscopy (≥50×) to assess hole-wall burrs and edge chipping, with acceptance criteria of burr length ≤0.05 mm and chipping diameter ≤0.1 mm. Internal damage inspection should utilize ultrasonic testing to detect microcracks and delamination. Performance validation should include random sampling for flexural strength and insulation resistance, with requirements of ≥400 MPa and ≥10¹² Ω, respectively.

Nonconforming products should undergo immediate root-cause analysis, followed by adjustments to drill selection or process parameters, forming a closed-loop “inspection–analysis–optimization” system to continuously improve drilling stability.

Although drilling-induced damage to FR4 may appear to be a minor manufacturing issue, it represents a major hidden risk to PCB reliability. As PCBs continue to evolve toward higher density, thinner profiles, and higher frequencies, drilling challenges will intensify, and damage-control requirements will become increasingly stringent. Only through continuous optimization of drilling processes and coordinated advancement in drill technology, equipment precision, and inspection methodologies can manufacturers safeguard PCB quality while maintaining productivity—thereby providing a robust foundation for end-product reliability.