In PCB soldering processes, the role of flux is indispensable. Without high-quality flux, even with premium solder and precision equipment, achieving acceptable solder joints remains challenging. Yet flux exhibits a pronounced dual nature—it is both the ‘hero’ of soldering and the ‘source’ of residual hazards. This characteristic is closely tied to flux composition, type, and application scenarios, forming the foundation for understanding flux residue risks.

The core components of flux comprise four principal categories: active substances, solvents, film-forming agents, and additives. Each category may serve as a potential trigger for residual hazards: Active substances (such as organic acids and halogen compounds) are responsible for removing oxide layers and constitute the core functional element of flux. However, these substances are often corrosive; if residues remain after soldering and are exposed to air and moisture over time, they may gradually corrode copper foil and solder joints. Solvents (e.g., ethanol, acetone) dissolve the active agents and film-forming agents, facilitating uniform flux application. If solvents fail to fully evaporate, they may remain in PCB circuit gaps, forming viscous residues that attract dust and impurities, indirectly causing short circuits. Film-forming agents (e.g., rosin, resins) create a protective layer over solder joints post-welding to reduce oxidation. However, inferior agents or those not fully cured may form uneven residues that compromise the PCB’s insulation properties. Additives (e.g., wetting agents, antioxidants) enhance soldering performance. Certain additives exhibit hygroscopic properties; residuals increase the PCB’s water absorption rate, accelerating corrosion.

Based on practical applications within the PCB manufacturing industry, flux can be categorised into three primary types: rosin-based, water-soluble, and no-clean. The residual characteristics and potential hazards of each type differ significantly, thereby dictating distinct cleaning requirements:

Rosin-based flux (classified as R, RA, and RMA types) is currently the most widely used type in PCB soldering. Primarily composed of natural rosin, it offers low cost and stable soldering performance, making it suitable for mid-to-low-end PCB products such as general consumer electronics and household appliances. Residues from this type are predominantly rosin resin, appearing pale yellow or brown with low viscosity. While exhibiting minimal short-term corrosion, prolonged use allows residual rosin to adsorb dust and moisture, gradually ageing and cracking. This leads to solder joint oxidation and impairs PCB thermal dissipation. Particularly in high-density PCBs, residues readily clog inter-track gaps, causing signal interference.

Water-soluble flux employs organic acids as its primary active agent. Offering high soldering efficiency and leaving no rosin residue, it is suitable for high-density, fine-pitch PCBs (such as those in mobile phones and tablets) and precision component soldering. The residual risks associated with this type of flux primarily stem from inadequately cleaned active ingredients and solvents. The active substances possess strong corrosive properties; if left behind, they may cause copper foil corrosion and solder joint discolouration within a short period. Moreover, water-soluble residues readily absorb moisture, accelerating circuit failure in high-humidity environments (such as southern rainy seasons or outdoor equipment). Therefore, thorough cleaning after soldering with this flux is essential, as residuals pose significant hazards otherwise.

No-clean flux is designed for high-end PCBs (e.g., automotive, medical, aerospace applications). It contains low levels of active substances with weak corrosivity, leaving minimal residue post-soldering. This residue layer exhibits excellent insulation and moisture resistance, eliminating the need for additional cleaning. However, no-clean flux is not entirely ‘residue-free’. Residual risks primarily stem from two sources: firstly, excessive residue resulting from improper application (such as over-application or insufficient soldering temperatures); secondly, residual active substances from inferior no-clean flux formulations. While such residues pose no immediate harm, they may gradually degrade under extreme conditions (e.g., high-low temperature cycling in automotive applications, high-temperature sterilisation in medical devices), leading to reliability issues. Consequently, the selection and proper application of no-clean flux directly determine the extent of residual risks.

The ‘Invisible Culprit’ Behind Flux Residue

Inappropriate selection serves as the root cause of flux residue hazards. Many PCB manufacturers focus solely on soldering performance and cost during selection, neglecting the compatibility between residue characteristics and application scenarios. Consequently, even with thorough post-processing cleaning, residual risks remain difficult to eliminate entirely. For instance, employing rosin-based flux for high-density, fine-pitch PCB soldering risks clogging interconnect gaps due to rosin’s adhesive residue, which persists even after cleaning. Similarly, using water-soluble flux for outdoor PCB products invites moisture absorption in residues; even after thorough cleaning, inadequate subsequent protection allows trace active substances to accelerate corrosion. Opting for substandard flux, characterised by unreasonable composition ratios, excessively high active substance content, and slow solvent evaporation rates, inevitably leads to substantial residue post-soldering. Such residues exhibit heightened corrosiveness and present greater challenges for removal.

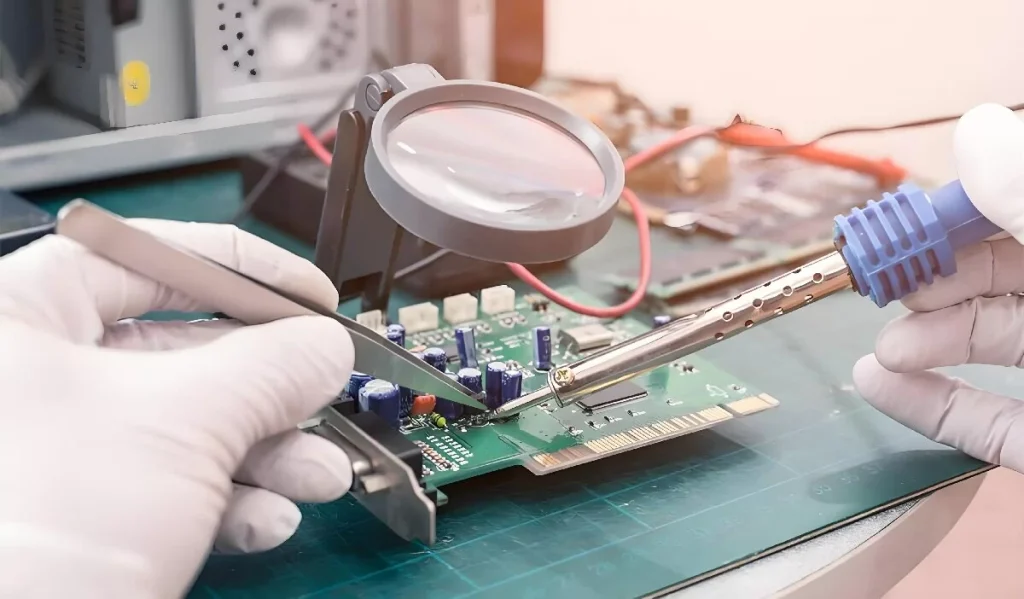

Non-standard application practices constitute the direct cause of residue formation and represent the most prevalent issue in PCB mass production. This manifests in three primary ways: Firstly, excessive flux application. Many operators indiscriminately increase flux quantity to ensure soldering pass rates, resulting in post-soldering residue exceeding permissible limits. Excess flux may overflow from joints, adhering to PCB surfaces and traces, thereby complicating cleaning procedures. Secondly, uneven application. Inconsistent flux distribution causes inadequate soldering in some areas and excessive residue in others. Particularly in automated soldering equipment, nozzle blockages or excessively rapid application speeds can lead to uneven coverage, creating localised residue hazards. Thirdly, flux degradation occurs when opened flux is improperly stored or used beyond its shelf life. This causes compositional changes, rendering active agents ineffective and leading to solvent evaporation. Post-soldering, this results in substantial solidified residues that are difficult to remove while also compromising soldering quality.

Unsuitable process parameters constitute an ‘indirect contributing factor’ to residue formation, often overlooked by PCB manufacturers. The three critical parameters of soldering temperature, time, and solder volume directly influence flux volatilisation and solidification, thereby affecting residue levels: – Insufficient soldering temperature (below 210°C) prevents complete solvent volatilisation and inadequate reaction of active components, leading to substantial residue accumulation; Excessively high soldering temperatures (above 260°C) cause flux carbonisation, forming black solidified residues. These residues are hard, highly adhesive, difficult to remove, and lose their insulating properties after carbonisation, increasing the risk of short circuits. Insufficient soldering time prevents the flux from fully activating, increasing residue while compromising joint integrity. Excessive soldering time causes over-evaporation of the flux, leading to joint oxidation and the formation of carbonised residues. Furthermore, excessive solder volume traps the flux within the solder, preventing evaporation and removal. This creates internal residues that gradually diffuse during prolonged use, causing joint failure.

Inadequate cleaning serves as the ‘ultimate trigger’ for residue hazards, representing the most readily identifiable yet most challenging issue to rectify. While many PCB manufacturers incorporate cleaning processes, residues often remain due to suboptimal cleaning techniques, outdated equipment, or non-standardised operator practices. For instance: Inappropriate solvent selection fails to dissolve residual flux components (e.g., ordinary alcohol cannot dissolve water-soluble flux activator residues); insufficient cleaning time or excessively low temperatures prevent complete dissolution of residues; failure to promptly dry PCBs post-cleaning leaves surface moisture that accelerates corrosion from residual components while causing secondary adhesion of residues.

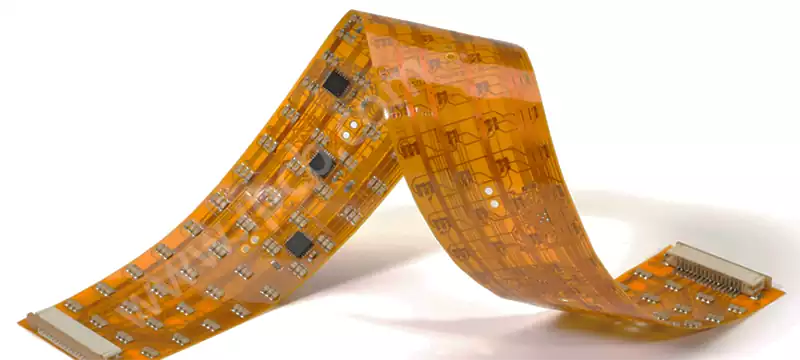

Furthermore, PCB structural characteristics exacerbate residue risks: – High-density, fine-pitch PCBs (line width/spacing < 0.15mm) feature narrow trace gaps where flux readily traps, making removal exceptionally challenging; PCBs incorporating precision components such as BGAs or QFPs present additional challenges. The gaps beneath these components and the PCB substrate often become inaccessible ‘blind spots’ for flux residues, beyond the reach of conventional cleaning methods. Over time, these residues gradually corrode solder joints, leading to component detachment and short circuits.

Dangers of Flux Residue to Circuit Board Performance

Corrosion Hazards

Corrosion represents the most prevalent and fundamental hazard posed by flux residue, constituting the primary cause of long-term circuit failure. This risk is significantly exacerbated in adverse conditions such as high humidity, elevated temperatures, or exposure to acids and alkalis, where corrosion rates accelerate dramatically, potentially causing irreversible damage within a short timeframe. The corrosive action of flux residues primarily stems from the interaction of residual active substances (organic acids, halogen compounds) with adsorbed moisture and oxygen, forming corrosion cells that progressively erode PCB copper foil, solder joints, and component leads.

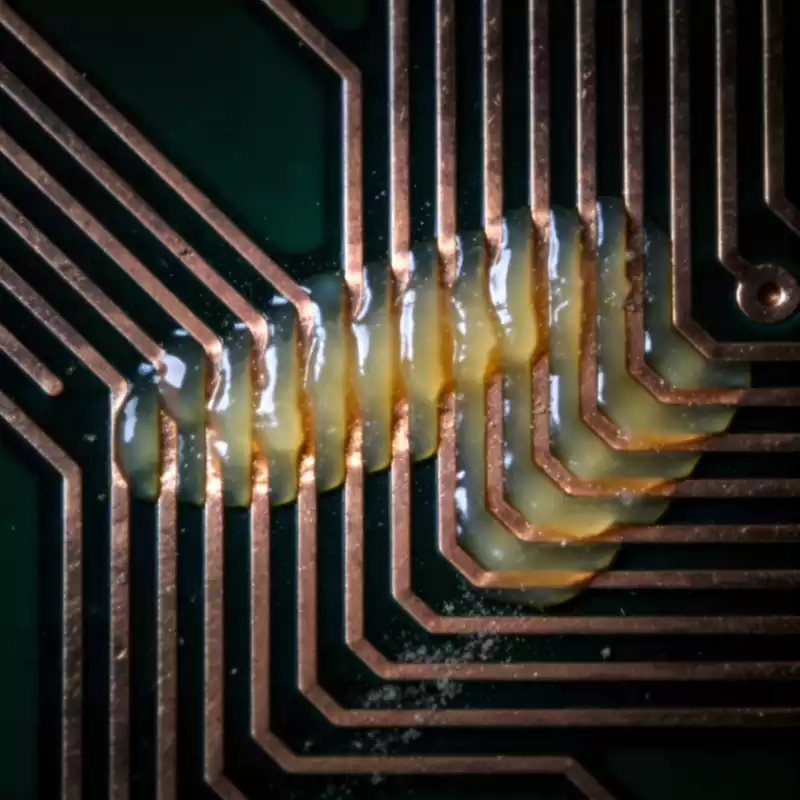

For PCB copper foil, residual active substances progressively dissolve the oxide layer on the foil surface while reacting chemically with the copper to form copper salts (such as copper sulphate or copper chloride). These substances possess a porous texture and poor conductivity, gradually coating the copper foil surface. This leads to reduced foil thickness and increased resistance, adversely affecting the circuit’s electrical conductivity. As corrosion intensifies, the copper foil may fracture or break, ultimately causing circuit interruptions and rendering the equipment inoperable. A household appliance PCB manufacturer once experienced batch failures. End-users reported frequent system crashes and black screens after one year of use. Inspection revealed extensive corrosion and fractures in the PCB copper foil. The root cause was excessive rosin-based flux residue. Upon absorbing moisture, the active substances gradually eroded the copper foil. Compounding the issue, the manufacturer omitted the cleaning process, allowing residues to accumulate over time.

For solder joints, flux residue corrosion causes oxidation, blackening, and detachment, compromising joint integrity and conductivity. As the critical interface between PCB and components, corroded joints lead to poor contact, abnormal resistance, or complete detachment—resulting in component failure and circuit breaks. Within automotive PCBs, prolonged exposure to thermal cycling and vibration environments amplifies the corrosive effects of flux residues. The active substances within these residues repeatedly expand and contract with temperature fluctuations, accelerating solder joint ageing and corrosion. This ultimately leads to failures in in-vehicle equipment (such as navigation systems and cameras), potentially compromising driving safety.

Hazards of Short Circuits

Short circuits represent the most perilous consequence of flux residue. Once initiated, they directly cause circuit burnout, equipment failure, and may even trigger fires or electric shock incidents. The risk is particularly acute in high-density, fine-pitch PCBs and high-voltage circuits. Flux residue induces short circuits primarily through two pathways, both intrinsically linked to residue characteristics and PCB architecture.

Solder Joint Failure

Solder joints form the core connections within PCB circuits, and their reliability directly determines the circuit’s long-term performance. Residual flux is one of the primary causes of long-term solder joint failure. While many PCB manufacturers focus on soldering pass rates, they often overlook the detrimental impact of residues on the long-term reliability of solder joints. This oversight leads to issues such as solder joint detachment and poor contact after a period of use.

Flux residue induced solder joint failure manifests in three primary ways: Firstly, residue corrodes the solder joint. As previously noted, residual active substances progressively erode the solder on the joint surface, causing oxidation, discolouration, and detachment, thereby compromising joint integrity. Secondly, residues impair joint adhesion. Post-soldering flux residues adhere between joints and pads, forming an isolating layer that hinders full solder-to-pad bonding. Over time, this layer degrades and fractures, causing joint-pad separation and resulting in poor contact or abnormal resistance values. Thirdly, residues cause fatigue failure in solder joints. Under conditions such as vibration or thermal cycling (e.g., in automotive or outdoor equipment), residual flux reduces joint toughness, inducing micro-cracks. Repeated vibration and temperature changes progressively widen these cracks, ultimately causing joint fracture and circuit disconnection.

The detrimental impact of flux residue on the long-term performance of PCB circuits cannot be overlooked. PCB manufacturers must fully recognise the potential hazards of flux residue during production, mitigate residual risks, enhance the long-term performance and reliability of PCB circuits, and ensure the quality and safety of electronic products.