Flexible PCBs, characterized by their bendability and ultra-thin form factor, break through the geometric constraints of traditional rigid boards, while rigid FR4 boards, relying on structural stability, low cost, and ease of processing, continue to dominate the mainstream market. From body-conforming wearable devices to structurally stable industrial control systems, each excels in its respective domain—often leaving design engineers facing difficult selection decisions. Flexible PCBs are not inherently more “advanced,” nor are FR4 rigid boards obsolete. Their true value lies in how well they match specific application requirements.

Material Fundamentals

Rigid FR4 boards are based on glass fiber–reinforced epoxy laminate copper-clad boards. Epoxy resin serves as the binder, woven glass fiber cloth provides mechanical reinforcement, and copper foil is laminated onto the structure. The defining characteristics of FR4 are high rigidity and excellent structural stability. The interwoven glass fiber fabric delivers strong mechanical strength and dimensional stability, while the epoxy resin ensures good electrical insulation and thermal resistance (typical FR4 Tg values range from 130–140 °C, with high-Tg variants exceeding 170 °C). These properties allow FR4 boards to reliably support a wide range of components and withstand the mechanical stresses of soldering and assembly processes.

Flexible PCBs, by contrast, are primarily based on polyimide (PI) or polyester (PET) films, laminated with copper foil using flexible adhesives. Polyimide is the dominant substrate due to its outstanding thermal resistance (Tg above 260 °C), chemical stability, and flexibility, enabling repeated bending without damaging the circuitry. Polyester substrates offer lower cost but inferior heat resistance (long-term operating temperatures ≤100 °C) and reduced flexibility, limiting them to less demanding applications. Because flexible PCBs lack rigid reinforcement layers, they inherently provide bendability, foldability, and extreme thinness, making them well suited for complex spatial layouts.

In terms of auxiliary materials, rigid FR4 boards typically use epoxy-based solder mask inks—most commonly green—to provide insulation and mechanical protection. Flexible PCBs require solder mask systems compatible with bending, often using flexible or polyimide-based coatings. In many cases, a coverlay is applied to further enhance bending endurance and insulation performance.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Flexible PCBs vs. Rigid FR4

1.Mechanical Performance

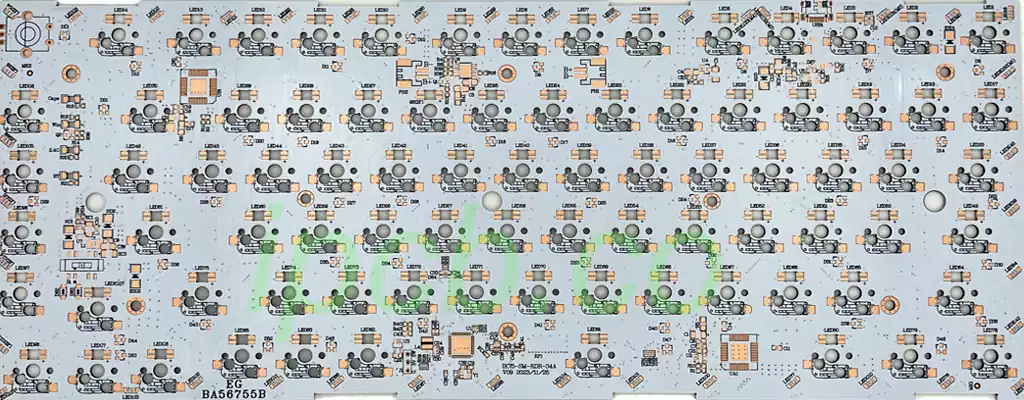

The primary advantage of flexible PCBs lies in their exceptional flexibility and lightweight construction. PI-based flexible circuits can achieve very small bending radii (typically 1–3 times the board thickness for inner bends) and tolerate repeated bending, folding, and twisting to accommodate complex three-dimensional layouts. Thicknesses can be reduced to below 0.1 mm, with weight only one-third to one-half that of equivalent FR4 boards—significantly reducing overall device mass, which is critical for ultra-thin designs. However, their lack of rigidity prevents them from independently supporting heavy components such as high-power ICs or large electrolytic capacitors. Reinforcement stiffeners are usually required; otherwise, deformation, solder joint failure, or trace damage may occur.

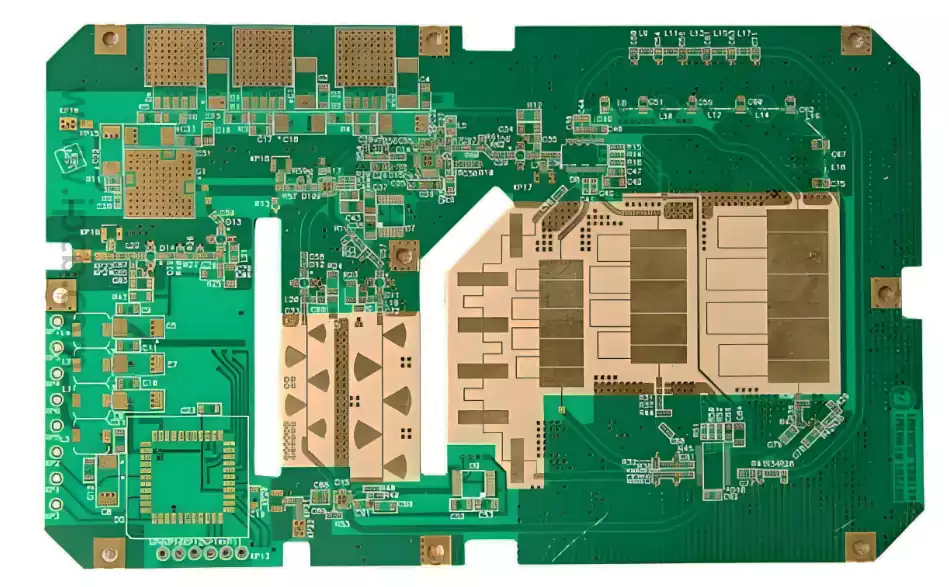

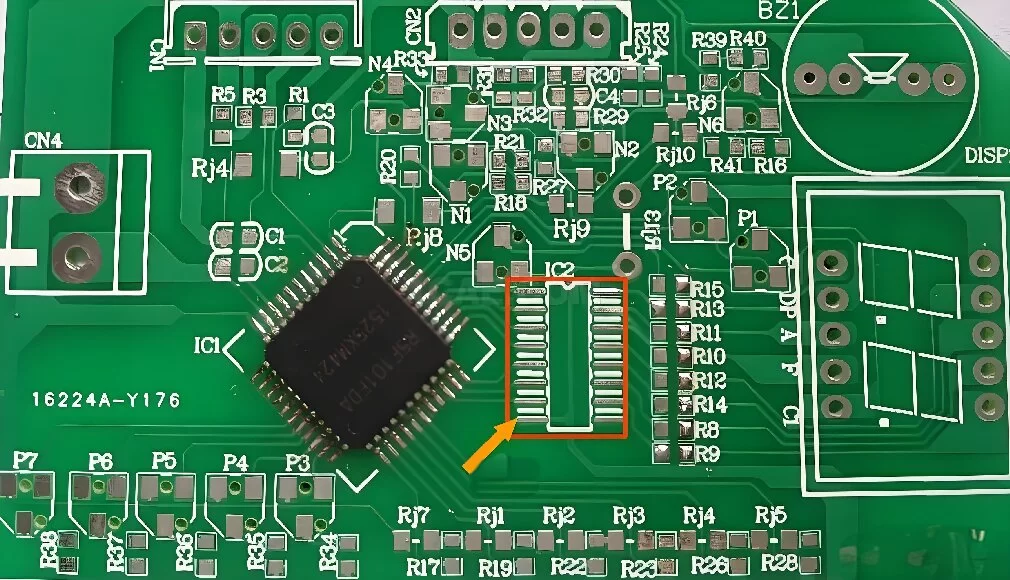

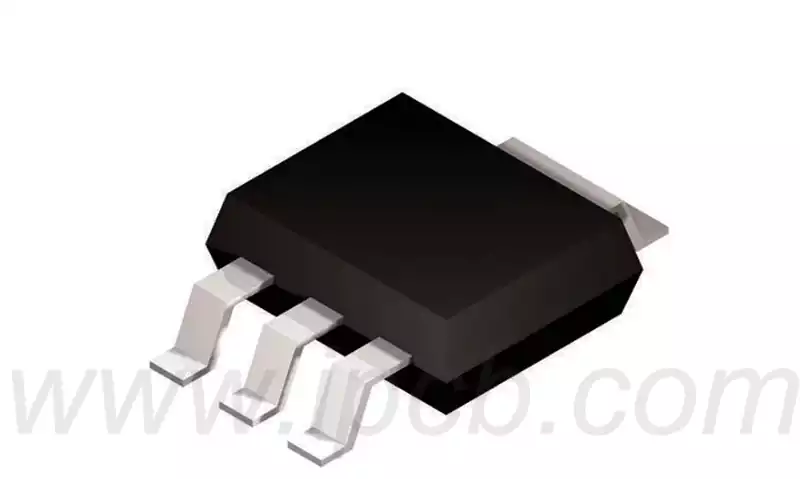

Rigid FR4 boards excel in mechanical strength and stiffness. Their resistance to bending, tension, and compression allows direct mounting of a wide range of components without additional reinforcement. Dimensional stability is excellent, with relatively low coefficients of thermal expansion (CTE), minimizing deformation during soldering and high-temperature operation. The main limitation of FR4 is its complete lack of flexibility: fixed geometry, typical thicknesses of 0.8 mm or greater, and higher weight restrict its use in ultra-thin or contoured product designs.

2.Electrical Performance

For high-frequency signal transmission, flexible PCBs—particularly those using PI substrates—offer certain advantages. Polyimide exhibits a relatively low dielectric constant (Dk ≈ 3.0–3.5) and low dissipation factor (Df ≈ 0.002–0.005), resulting in reduced signal attenuation and crosstalk, making it suitable for 5G, millimeter-wave, and other high-frequency applications. Its excellent thermal resistance also supports high-temperature soldering and continuous operation above 200 °C. However, the fine line spacing typical of flexible circuits can increase the risk of creepage and insulation issues in high-voltage applications, requiring careful design control.

Rigid FR4 boards provide balanced and reliable electrical performance. Standard FR4 materials have a dielectric constant of approximately 4.2–4.8 and a dissipation factor of 0.015–0.02, sufficient for low- to mid-frequency signal applications. Specialized variants—such as high-Tg or low-loss FR4—can extend performance into moderately high-frequency ranges. FR4 also offers stable insulation properties and easier control of creepage distances, making it better suited for high-voltage and high-current applications such as industrial control and power electronics. Nevertheless, standard FR4 exhibits higher signal loss at high frequencies compared with PI-based flexible circuits.

3.Manufacturing Process and Cost

Rigid FR4 benefits from mature, standardized manufacturing processes and low production costs. Drilling, etching, and solder mask printing are well-established, supported by widely available equipment and materials, making FR4 ideal for high-volume production. Raw material availability is stable, and the cost per unit area is typically only one-third to one-fifth that of flexible PCBs. However, complex shapes and intricate routing increase processing costs and material waste, often requiring CNC milling or additional post-processing steps.

Flexible PCB manufacturing is more complex and costly. Thin, pliable substrates demand high-precision drilling, etching, and coverlay lamination using specialized equipment and fixtures. Additional processes—such as stiffener attachment and coverlay bonding—further increase cost. Polyimide materials are inherently expensive, resulting in per-unit-area costs three to five times higher than FR4. That said, flexible PCBs enable integrated designs that reduce connectors and wiring, potentially lowering overall system assembly costs and offering advantages for low-volume, customized, or space-constrained products.

4.Reliability and Environmental Resistance

PI-based flexible PCBs demonstrate excellent environmental resistance. Polyimide withstands chemical exposure, radiation, and aging, supporting long service life in demanding applications such as aerospace and automotive electronics. However, flexible circuits are more susceptible to mechanical wear and bending fatigue; repeated flexing can eventually cause copper trace cracking or adhesive degradation. Reliability must therefore be ensured through optimized trace design, controlled bend zones, and protective layers.

Rigid FR4 reliability is highly dependent on environmental conditions. It performs well under mechanical stress and impact in standard industrial and consumer environments. However, prolonged exposure to chemicals, high humidity, or elevated temperatures can lead to material degradation, delamination, or blistering if not properly protected. Selecting high-Tg FR4 and applying appropriate protective coatings can significantly improve durability in harsh conditions.

Application Domains

Applications of Flexible PCBs

Wearable Devices: Smartwatches, fitness bands, and foldable smartphones rely on flexible PCBs to conform to body contours or folding structures, enabling miniaturization and complex form factors. For example, flexible circuits embedded in watch straps connect sensors to the main board without restricting wearability.

Automotive Electronics: Instrument clusters, infotainment systems, and sensor modules benefit from flexible PCBs that adapt to confined and curved interior spaces, reducing wiring and connectors while improving assembly efficiency and reliability.

Aerospace and Medical Devices: Weight and space constraints make flexible PCBs ideal for aerospace systems, while medical devices such as portable monitors and endoscopes leverage their compactness, thermal stability, and environmental resistance.

High-Frequency Communication Equipment: In 5G base stations and millimeter-wave radar, the low dielectric loss of PI-based flexible PCBs minimizes signal attenuation and supports complex internal routing.

Applications of Rigid FR4 Boards

Consumer Electronics: Smartphone mainboards, computer motherboards, and TV control boards depend on FR4’s structural stability and cost efficiency to support dense component populations in high-volume production.

Industrial Control Systems: Inverters, servo drives, and PLCs require the mechanical strength and electrical insulation of FR4 to handle harsh environments, high voltages, and high currents.

Power Modules and Energy Storage Systems: Power adapters and inverters benefit from FR4’s controlled creepage distances, stable insulation, and thermal performance under high electrical loads.

Home Appliances and Security Equipment: Cost-sensitive products such as refrigerators, air conditioners, and surveillance cameras favor FR4 for its low cost, simple structure, and reliable baseline performance.

The “flexibility” of flexible PCBs and the “rigidity” of FR4 boards do not represent a hierarchy of technologies, but rather two complementary responses to different design requirements. Flexible PCBs expand design possibilities, enabling thinner, lighter, and more contoured electronic products. Rigid FR4 boards, with their stability, reliability, and cost advantages, continue to underpin large-scale electronics manufacturing worldwide.

Looking ahead, advances in materials science are expected to reduce the cost of flexible PCBs while further enhancing FR4 performance. Although the boundary between the two may gradually blur, the fundamental principle of matching the technology to the application will remain unchanged—together driving electronics toward greater intelligence, compactness, and reliability.