The thermal conductivity coefficient of FR4 serves as a parameter for assessing the thermal performance of FR4 material (glass fibre reinforced epoxy resin). This coefficient is not a fixed absolute value but falls within specific industry standard ranges, exhibiting variations influenced by factors such as substrate formulation and manufacturing processes. According to international standards and industry practice, the thermal conductivity of conventional FR4 substrates ranges from 0.2 to 0.3 W/(m·K). While this value may appear low, it adequately meets the heat dissipation requirements of the vast majority of medium-to-low power electronic devices.

In practical applications, the thermal conductivity of standard FR4 adequately supports low-to-medium power modules in consumer electronics, such as standard control modules in smartphones or signal processing units in computer peripherals. In these scenarios, components operate at low power levels (typically below 1W per component), generating minimal heat. Temperature equilibrium is achieved through the inherent thermal conduction of the FR4 substrate and natural dissipation via the PCB surface. However, in high-power scenarios—such as drive modules in industrial control systems or power device units in automotive electronics—the thermal conductivity limitations of conventional FR4 become apparent. Here, enhanced thermal management necessitates design optimisation, including the addition of heat-dissipating vias or the adoption of high-thermal-conductivity FR4.

Notably, the advent of high-thermal-conductivity FR4 substrates has expanded FR4’s application boundaries in high-power scenarios. By incorporating high-thermal-conductivity fillers (such as aluminium oxide or boron nitride) into the epoxy resin matrix, the thermal conductivity of high-thermal-conductivity FR4 is elevated to 0.8–2.0 W/(m·K), with some premium variants exceeding 3.0 W/(m·K). While the thermal conductivity of such substrates remains inferior to metals, it represents a 3-10-fold improvement over conventional FR4. This enables effective adaptation to the thermal management demands of medium-to-high power applications, while retaining FR4’s electrical performance and cost advantages.

Core Factors Influencing FR4 Thermal Conductivity

1.Epoxy Resin System Formulation.

The inherently low thermal conductivity of epoxy resin (pure epoxy resin exhibits approximately 0.15–0.2 W/(m·K)) constitutes the fundamental constraint on FR4’s overall thermal performance. Conventional FR4 employs standard bisphenol A epoxy resin, resulting in limited thermal efficiency; High-thermal-conductivity FR4 optimises formulations by incorporating high-thermal-conductivity inorganic fillers. The type, particle size, and loading of these fillers directly determine the extent of thermal enhancement. For instance, adding micron-sized aluminium oxide filler (thermal conductivity ~30 W/(m·K)) can elevate FR4 thermal conductivity to over 1.0 W/(m·K) at a 50% loading; Adding nanoscale boron nitride filler (thermal conductivity approximately 400 W/(m·K)) achieves a similar enhancement with only 30% loading, though at a comparatively higher cost.

2.Specifications and weaving methods of glass fibre cloth.

Glass fibre cloth possesses a thermal conductivity of approximately 1.0–1.5 W/(m·K), exceeding that of epoxy resin. Its distribution state within FR4 significantly impacts thermal performance. Coarse-yarn glass fibre cloth (e.g., Type 7628) features larger fibre diameters, enabling more unobstructed thermal pathways. Compared to fine-yarn glass fibre cloth (e.g., Type 1080), it can enhance the thermal conductivity of FR4 by approximately 10%-15%. Plain-woven glass fibre cloth exhibits uniform warp and weft density, resulting in more stable thermal conductivity. Conversely, twill-woven fabrics feature directional fibre distribution, potentially causing variations in FR4 thermal conductivity across different orientations (typically within 5%-8%).

3.Optimisation of production processes.

The lamination process is a critical production stage affecting FR4 thermal conductivity. High-temperature, high-pressure process parameters directly determine the substrate’s internal density and interfacial bonding strength. Insufficient lamination temperature or pressure can create internal voids (porosity exceeding 2%). Air possesses an extremely low thermal conductivity (approximately 0.023 W/(m·K)), severely impeding heat transfer and reducing thermal conductivity. Conversely, optimising lamination parameters (e.g., raising temperature to 180°C and pressure to 3.0 MPa) can reduce porosity below 1% and enhance interfacial bonding. This facilitates smoother heat transfer between resin and fibres, thereby improving overall thermal conductivity.

The Core Function of Thermal Via Holes

When the thermal conductivity of the FR4 substrate itself fails to meet heat dissipation requirements, thermal vias become the most commonly employed thermal design optimisation technique. The core function of thermal vias is to establish ‘vertical thermal pathways’, conducting heat generated by components on the PCB’s top or bottom layer through the metal plating within the via to another layer. Alternatively, via arrays can distribute heat across a larger area of the PCB, thereby enhancing dissipation efficiency. Compared to conventional surface heat dissipation methods, thermal vias overcome the limitations of FR4 substrate’s low thermal conductivity, enabling cross-layer heat transfer and rapid diffusion. They are an indispensable critical element in high-power PCB design.

From a thermal conduction perspective, the metal plating (typically copper, with a thermal conductivity of approximately 401 W/(m·K)) within thermal vias establishes highly efficient thermal pathways, significantly outperforming the FR4 substrate itself. For instance, a copper-plated heat dissipation via measuring 0.8mm in diameter and 1.6mm in depth possesses vertical thermal conductivity equivalent to a 100mm × 100mm × 1.6mm area of FR4 substrate, substantially enhancing local heat transfer efficiency. Furthermore, heat dissipation vias can integrate with heat sink pads and copper cladding designs to form a complete thermal chain: ‘component → heat sink pad → heat dissipation via → large-area copper cladding’. This facilitates rapid heat diffusion from high-temperature zones to cooler areas, achieving thermal equilibrium.

It must be emphasised that thermal vias are not simply a case of ‘more being better’. Unreasonable via design may degrade the PCB’s electrical performance (such as affecting impedance matching or increasing signal crosstalk), while simultaneously increasing manufacturing complexity and cost. Therefore, accurately determining ‘when thermal vias should be added’ is central to achieving a balance between thermal and electrical design.

When should thermal vias be added?

1.High-power components mounted directly on the surface of an FR4 PCB.

When a single component exceeds 1W power, the thermal conductivity of standard FR4 substrates becomes insufficient to dissipate heat promptly, potentially causing excessive temperature rise beneath the component. Components such as power transistors and LED driver chips generate significant heat during operation. Relying solely on surface cooling may cause temperatures to exceed the component’s maximum tolerance (typically 125°C). In such cases, a heat dissipation via array must be positioned beneath the component’s heat sink pad to conduct heat to another layer of the PCB, where it is dissipated via a large copper plane. Experimental data indicates that placing four 0.6mm diameter heat dissipation vias beneath a 1W LED chip reduces the chip’s base temperature by 25°C-30°C, significantly enhancing operational stability.

2.High PCB layout density restricts thermal dissipation space.

PCBs in consumer electronics (e.g., smartphones, tablets) typically employ high-density layouts with minimal component spacing (less than 2mm), facilitating localised heat accumulation and ‘hotspot’ formation. Even when individual components have low power ratings (0.5-1W), densely packed arrays can achieve total power densities exceeding 2W/cm² in localised areas. Conventional FR4 materials lack sufficient thermal conductivity to rapidly dissipate this heat, leading to excessive hotspot temperatures. In such cases, thermal vias must be placed around the hotspot to distribute heat across the PCB and prevent accumulation. For instance, smartphone processors typically feature densely arranged heat dissipation via arrays, working in tandem with metal mid-frames to facilitate rapid heat dispersion.

3.Operating in high ambient temperatures with poor thermal conditions.

Certain electronic devices must function in high-temperature environments (e.g., automotive engine compartments, industrial high-heat workshops), where ambient temperatures may exceed 85°C. Under such conditions, the thermal efficiency of FR4 PCBs diminishes due to reduced thermal differential, potentially causing overheating even in medium-to-low power components. In such cases, adding heat dissipation vias is necessary to enhance thermal conductivity, ensuring component temperatures remain within maximum tolerance limits. For instance, in automotive electronics, the Engine Control Unit (ECU) utilises an FR4-based PCB. Within the 85°C engine compartment environment, power components require heat dissipation vias to facilitate cooling in conjunction with a metal heat sink, thereby preventing control failures caused by excessive heat.

4.Temperature test results exceed specifications.

Through thermal simulation or actual testing, it was discovered that the local temperature of the FR4 PCB exceeded the maximum tolerance temperature of the components or surpassed the design threshold (typically 85°C). In such cases, thermal vias must be added for optimisation. Temperature testing provides the most direct basis for determining the necessity of thermal vias. Even if components have low power ratings and layout density is not high, exceeding temperature limits during actual testing necessitates enhancing thermal dissipation through design measures such as thermal vias. For instance, in a relay module of an industrial control PCB, each relay consumed only 0.8W. However, testing revealed surrounding temperatures reaching 92°C, exceeding the design threshold. After adding three heat-dissipating vias, the temperature dropped to 78°C, meeting design requirements.

Design Considerations for FR4 PCB Thermal Via Holes

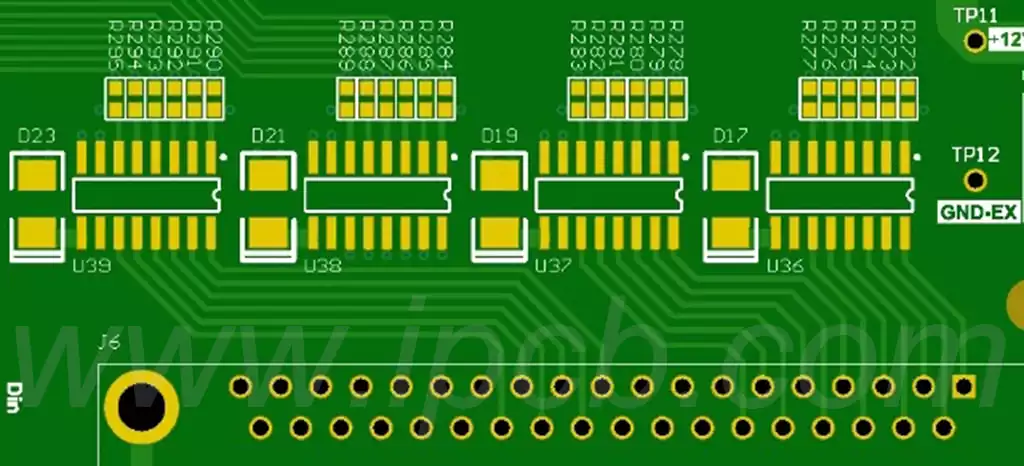

Via hole selection must align with thermal requirements and PCB structure. Two primary types are employed: through holes and blind holes. Through holes penetrate the entire PCB, offering the longest thermal path and optimal heat dissipation, suitable for scenarios requiring inter-layer heat transfer (e.g., power modules in multilayer FR4 PCBs). Blind vias penetrate only one or several layers of the PCB, suitable for scenarios without interlayer heat transfer (e.g., localised hotspot dissipation in double-layer PCBs). Their advantage lies in not occupying layout space on other layers, thereby avoiding interference with component placement. For high-density FR4 PCBs, buried vias may also be employed, concealing the vias within the PCB to further enhance layout space utilisation. However, this involves more complex manufacturing processes and relatively higher costs.

Dimensional parameter settings must balance thermal performance with manufacturing feasibility. The diameter and plating thickness of thermal vias are critical parameters affecting heat dissipation: larger diameters increase the metal plating area within the via, enhancing thermal conductivity. For standard FR4 PCBs, thermal via diameters are recommended between 0.4–1.0mm. Diameters exceeding 1.0mm may occupy excessive layout space and potentially compromise PCB mechanical strength. The plating thickness should ideally not be less than 20μm. Excessively thin plating (below 15μm) increases resistance within the thermal path, diminishing heat dissipation efficiency. Additionally, via spacing must be appropriately configured. For via arrays, spacing should ideally be 2-3 times the via diameter (e.g., 1.2-1.8mm spacing for 0.6mm diameter vias), ensuring even heat dispersion and preventing thermal dead zones.

Layout optimisation must complement the establishment of thermal pathways. Thermal vias should be positioned as close as possible to the heat sink pads of heat-generating components, ideally connected directly to them. This minimises thermal conduction paths and prevents heat loss during transfer. For high-power components (e.g., power transistors), a ‘ring-shaped via array’ is recommended: arrange a ring of vias around the component’s heat sink pad to create a comprehensive thermal conduction pathway, thereby enhancing heat dissipation efficiency. Concurrently, the opposite end of the thermal vias must connect to a large copper plane (with an area no less than five times that of the via array). This copper plane facilitates rapid heat dispersion; otherwise, heat conducted through the vias will accumulate at the opposite end, preventing effective dissipation.

The thermal conductivity of FR4 is not an absolute ‘weakness’ but rather a performance metric requiring precise application-specific assessment. Conventional FR4’s thermal conductivity of 0.2–0.3 W/(m·K) adequately supports low-to-medium power scenarios, while high-thermal-conductivity FR4 expands application boundaries for high-power scenarios through material optimisation. Thermal vias, as a key design element to address FR4’s thermal limitations, must be implemented based on scientifically informed scenario assessments to avoid indiscriminate design practices.