The Fundamental Concepts and Industry Significance of IC Chip Sockets

In modern electronic systems, chips are constantly evolving towards higher integration levels, more refined manufacturing processes, and more complex packaging, and the corresponding connection methods are also upgrading accordingly. In the entire electronic manufacturing system, the IC chip socket is a device that is often overlooked but plays a crucial role at critical junctures. Its core function is to provide a pluggable, replaceable, and testable intermediate interface for integrated circuits (ICs), enabling reliable electrical connections between the chip and the PCB without the need for permanent soldering. This seemingly simple structure is indispensable in scenarios such as high-precision testing, protection of high-value chips, and rapid development and verification. Its importance is not only reflected in the manufacturing stage but also permeates R&D, laboratory debugging, pre-mass production verification, and after-sales fault analysis.

The basic form of an IC chip socket consists of a housing, contact terminals, a fixing structure, and a positioning device, while the key internal technologies focus on contact materials, terminal structures, spring deformation performance, and thermal expansion adaptability. With the continuous shrinking of chip pin pitch and the widespread application of packages such as BGA/LGA/QFN, traditional pin-type sockets can no longer meet the stability requirements of modern electronic products. The industry is gradually moving towards interface solutions with higher precision, higher heat resistance, and stronger compatibility. For design engineers, purchasing personnel, and manufacturing companies, a deep understanding of the socket mechanism and its impact on product reliability is a prerequisite for ensuring the stability of overall system performance.

The value of IC chip sockets in the entire electronics industry chain goes beyond just “connection”; they also play the role of “protector.” For expensive chips with long development cycles, once soldered onto a PCB, disassembly can cause irreversible damage. Using sockets avoids the risks of direct soldering, making them particularly suitable for applications involving repeated plugging and unplugging, continuous testing, or frequent changes in experimental solutions. Furthermore, it provides factories with more flexible production methods, especially in industries with rapid initial trial production or product iteration. Sockets can help factories avoid wasting large amounts of chips and PCBs due to design adjustments, improving resource utilization efficiency.

From a macro perspective, the development trend of IC chip sockets is highly correlated with the technological evolution of the entire electronics industry. In fields such as AI, high-frequency communication, automotive electronics, satellite communication, and wearable devices, chips are advancing towards higher reliability and longer lifespan. As a crucial connection element, sockets are also evolving towards higher density, higher temperature resistance, lower contact resistance, and compatibility with multiple packaging forms. They are not only accessories for electronic hardware but also fundamental modules that constitute high-quality electronic systems.

IC Chip Socket Structural Design and Core Technology Details

While the design of an IC chip socket may appear superficially as a simple component made of plastic and metal, it actually involves multiple dimensions of technology, including mechanical structure, materials engineering, thermodynamics, electrical contact theory, and packaging process matching. To achieve stable and reliable insertion and removal lifespan, low-loss transmission, and structural integrity under high-temperature environments, each internal component undergoes rigorous design and precise manufacturing. The following analysis delves into the core technologies and industry concerns of a socket, starting with its key components.

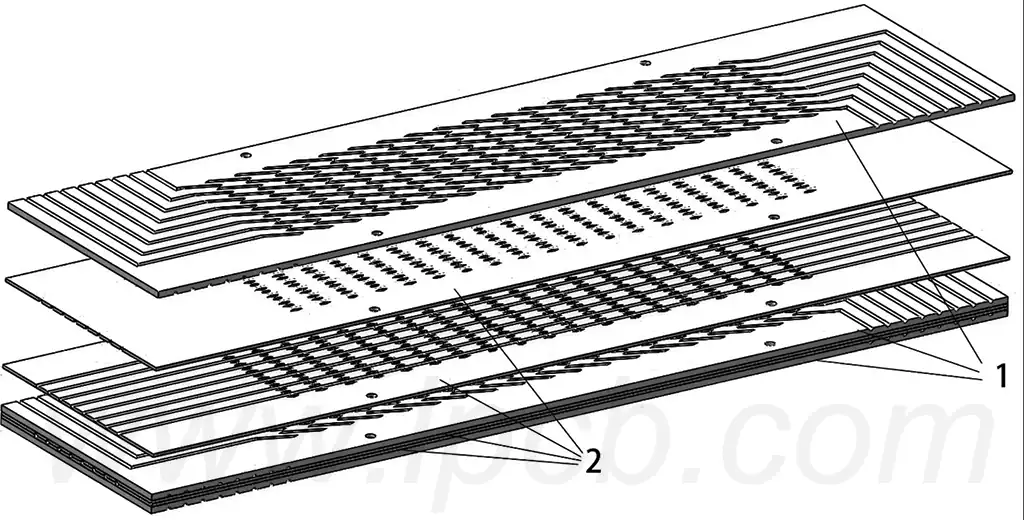

First, the overall framework structure of the socket determines the types of packages it can support and its mechanical stability. The housing is typically made of high-temperature resistant, high-dimensionally stable engineering plastics, such as LCP, PEEK, or PPS, because sockets may be exposed to temperatures of 125°C or even higher during testing and application, and must withstand the physical stress from repeated insertions and removals. The glass transition temperature of the engineering plastic and the dimensional changes of the material under thermal cycling directly affect the precision alignment capability, especially in high-density packages such as BGA and LGA. Even slight deformation of the plastic housing can lead to contact point misalignment, resulting in poor contact or intermittent failure.

Secondly, the connection terminals are the core technology of the entire socket. Terminal materials are generally beryllium copper, phosphor bronze, or highly conductive copper alloys, and gold, palladium-nickel, or tin plating processes are used to improve corrosion resistance and contact performance. The geometry of the terminals is a key factor in socket precision; factors such as spring angle, contact surface width, and the location of stress concentration areas all require precision stamping or etching processes. A high-quality terminal must maintain linear elastic deformation under pressure and maintain stable contact pressure without fatigue fracture after thousands of insertions and removals.

Contact resistance is one of the most critical metrics for technical engineers. To ensure minimal loss during high-frequency signal transmission within a socket, terminals must maintain ultra-low contact resistance. This depends not only on the conductivity of the metal material itself but also on the stability of the terminal structure design, the adequacy of the crimping pressure, the uniformity of the plating thickness, and whether the surface roughness is within acceptable limits. In high-speed communication, millimeter-wave applications, and RF testing, every 1 mΩ increase in contact resistance can lead to a degrade in system performance or distortion of the test signal waveform. Therefore, socket manufacturers typically conduct rigorous testing and screening of the electrical properties of their terminals.

Furthermore, to accommodate different package types, sockets incorporate various positioning and guiding mechanisms. For BGA packages, guide pillars and precision holes are commonly used to ensure accurate alignment of the chip solder balls with the terminals. For QFN or LGA packages, peripheral limiting structures and flexible contact surfaces are relied upon to ensure the chip is pressed flat against the socket. The guiding structure not only affects the ease of insertion and removal but also determines whether long-term use will easily cause chip edge wear or damage to the solder balls due to excessive force.

Thermal design is also a hidden technical hurdle for sockets. In high-power chip testing, chip operating temperatures rise rapidly, so sockets must provide excellent heat dissipation channels. Common methods include open-bottom structures, embedded metal heat sinks, thermally conductive adhesive, or heat dissipation airflow designs. Poor thermal design can lead to frequency drops, increased data errors, and even package warping due to localized overheating. Similarly, if a socket cannot withstand thermal expansion and contraction cycles, it will accelerate terminal fatigue and shorten its overall lifespan.

In practical engineering applications, sockets must also possess a certain degree of maintainability. For example, high-end test sockets often employ replaceable terminal designs, allowing engineers to restore contact performance without replacing the entire socket. While this design increases cost, it greatly enhances flexibility in R&D and testing scenarios and improves the long-term value of the socket.

In summary, the structural design of an IC chip socket is far more complex than its external appearance suggests. It must simultaneously meet mechanical precision, electrical performance, thermal adaptability, and long-term reliability within a limited space, and each of these indicators directly impacts the stability of the final product. This is why experienced engineers evaluate sockets from multiple aspects, including materials, plating, electrical performance, structural design, and insertion/removal lifespan, when selecting one. The quality of the socket determines whether the chip can maintain a stable connection throughout its entire product lifecycle.

Main Types and Application Differences of IC Chip Sockets

The types of IC chip sockets are not determined by their appearance, but rather by the compatible package structure, electrical characteristics, mounting method, testing frequency, and long-term usage patterns. Different types of sockets differ significantly in design philosophy, manufacturing difficulty, application scenarios, and performance. Understanding these differences helps engineers and purchasing personnel select the most suitable interface solution in R&D, production, or testing environments, and avoids unnecessary risks or cost waste due to improper selection.

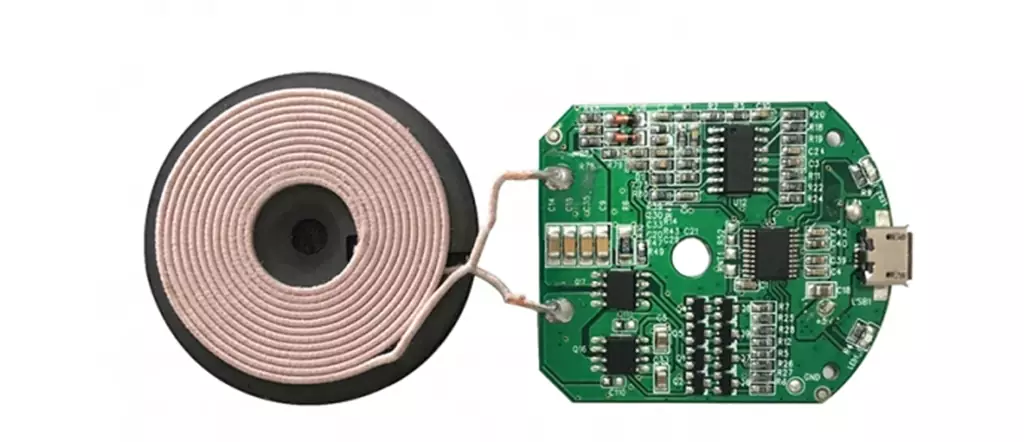

Firstly, from a package perspective, the most common socket types include those compatible with BGA, LGA, QFN, SOP, and DIP packages. BGA sockets are typically used in high-density, high-performance chips, such as FPGAs, CPUs, or high-speed network processors. These types of sockets have a precise, elastic contact structure, requiring the solder balls to provide uniform pressure and stable contact without damage. Therefore, their mechanical structure and guiding components have extremely high precision requirements. In contrast, LGA sockets have terminals that directly contact the metal pads on the bottom of the chip, demanding even stricter flatness control and relying more heavily on the electrical properties of the terminal materials in high-frequency applications to reduce signal reflection and transmission loss at the contact points.

QFN sockets are frequently used in consumer electronics and miniaturized terminal product development. They are characterized by the chip itself having no exposed pins, providing only metal pads on the bottom. To ensure stable contact between these pads and the socket’s elastic terminals, manufacturers often incorporate elastic top covers, pressure distribution plates, or micro-spring structures within the socket to prevent poor contact due to uneven pressure. DIP and SOP sockets, on the other hand, are more traditional and are mostly used in educational experiments, low-end controller modules, and some pluggable control cards. These sockets are easy to insert and remove, but due to their large pin pitch and generally lower electrical performance, they are not suitable for high-frequency or high-speed products.

From an application perspective, sockets can be categorized into test sockets, programming sockets, mass production sockets, and long-term use sockets. Test sockets are the most technically demanding, requiring the ability to withstand high-frequency signals, frequent insertions and removals, and harsh temperature cycling. They are commonly used for laboratory verification, high-speed interface testing, and chip characteristic evaluation. Test sockets must have extremely low and highly stable contact resistance, as even minor variations can affect measurement accuracy, and their cost is often higher. Programming sockets focus on firmware writing, emphasizing durability and insertion/removal efficiency, especially for automated programming equipment. Therefore, their shape, guide structure, and contact terminals must support mechanized operation.

Mass production sockets are typically used in the factory’s functional testing phase (FT, ICT, or EOL testing), where lifespan and testing speed are key considerations. Compared to test sockets, their bandwidth requirements may not be as high, but they must possess good abrasion resistance and a maintainable structure to ensure stable performance over tens of thousands of insertions and removals. Long-term sockets used in product assembly are commonly found in server CPUs, industrial controller modules, and automotive ECUs, allowing users to directly replace chip modules when needs change or upgrades are required. These sockets emphasize long-term reliability, mechanical strength, and shock resistance, and are typically the most complex in structure, involving more safety standards.

From a signal characteristics perspective, the design of different sockets also varies depending on the frequency range. High-frequency applications (such as 5G, radar, and millimeter-wave communication) require sockets with excellent impedance control and extremely low parasitic effects; otherwise, signal reflection and transmission loss will occur. High-speed digital applications such as PCIe, DDR, and SerDes also require sockets to maintain low insertion loss and consistency during high-speed conversions. Sockets used for low-speed logic or general MCUs focus more on cost and mechanical durability, and do not require expensive high-frequency materials.

In the industrial field, IC chip sockets are also classified according to their temperature range. Sockets used for high-temperature programming or automotive electronics verification must withstand long-term operating temperatures above 150°C and maintain the elasticity of the metal contacts during temperature shocks (−40°C to +150°C). Sockets used for consumer electronics debugging typically only need to meet medium temperature requirements, significantly reducing material and manufacturing costs.

In summary, socket type classification reflects not only product form but also the electrical, structural, and durability requirements of different applications. For engineers, clearly defining the application scenario and selecting the most suitable socket type can significantly improve work efficiency, reduce debugging risks, ensure testing accuracy, and improve yield and reliability in mass production. For enterprises, accurate selection can also reduce unnecessary trial-and-error costs and make project schedules more controllable.

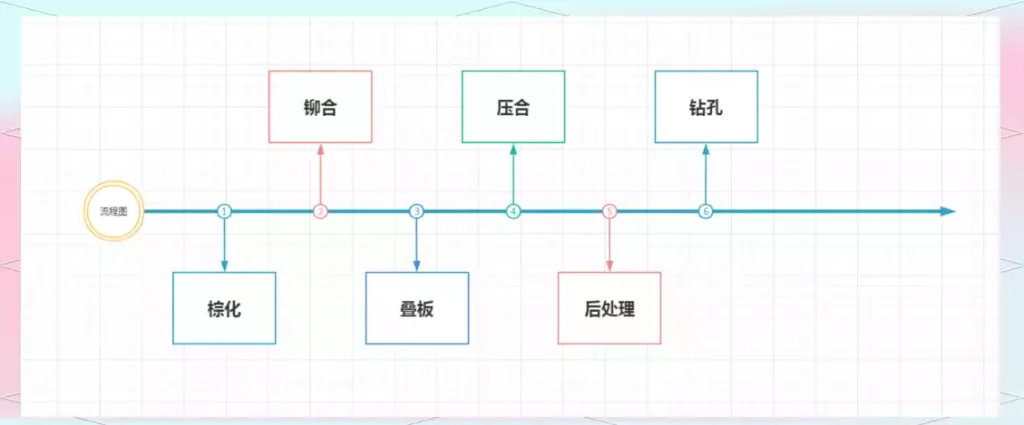

The Key Role of IC Chip Sockets in Manufacturing Processes and Testing Flows

The value of IC chip sockets in electronic manufacturing and testing flows far exceeds the “pluggable connection” itself. They permeate the entire process, from R&D verification and engineering pilot production to mass production testing and post-maintenance, and are a crucial link in ensuring that chip functionality is accurately verified time and time again and that product performance is delivered stably. As the electronics industry becomes increasingly complex and product cycles shorten, sockets are evolving from simple tools into a crucial bridge between connectivity technology, test engineering, and production efficiency. Understanding their true role requires in-depth analysis of their unique function across multiple practical processes and testing environments.

Firstly, in the R&D phase, engineers need to perform functional verification, performance boundary analysis, temperature behavior testing, and signal integrity analysis on new chips. At this stage, chips are often in a state of continuous modification or updating. If each test requires soldering the chip onto the PCB, it not only introduces time-consuming soldering procedures but also increases the risk of chip damage. Sockets allow engineers to perform highly efficient repeated insertion and removal, quickly switching between different test boards, load conditions, and firmware versions, significantly improving R&D speed. This is particularly important in areas requiring extensive iterative testing, such as high-end FPGAs, AI inference chips, and RF front-end modules. A well-designed socket maintains stable contact resistance, enabling engineers to obtain accurate and repeatable data, thus avoiding misjudgments due to poor contact.

In the engineering pilot production phase, sockets serve as crucial transitional tooling. When a product moves from prototype to small-batch trial production, the design may still undergo minor tweaks, such as changes to PIN definitions, power architecture optimization, or thermal structure adjustments. If these changes directly affect chip soldering methods, they can lead to significant rework and material waste. Sockets can act as a “buffer layer” at this stage, providing a solderless mounting structure for chips that may still require adjustments. This allows the factory to perform process verification, fixture testing, and functional debugging first, avoiding additional costs from repeated soldering modifications.

In the mass production testing phase, IC chip sockets once again play a crucial role. Modern electronics manufacturing processes, including end-of-life (EOL) testing, in-circuit testing (ICT), functional testing (FT), and high-speed interface verification, all rely on durable, precise, and long-life sockets to handle numerous repetitive insertion and removal operations. The biggest challenge in mass production

The reliability of test data hinges on testing efficiency and yield stability, and the consistency of socket contact directly determines the reliability of the test data. Poor socket design can lead to increased contact resistance after thousands of insertions and removals, potentially causing misjudgments that render good products unusable or allowing defective products to enter the supply chain. Therefore, high-end mass-production test sockets often require replaceable terminals, lifespan monitoring mechanisms, and wear-resistant plating to maintain long-term electrical stability.

In high-frequency and high-speed applications, sockets are indispensable signal channels in the test chain. Test equipment for devices such as 5G modules, millimeter-wave RF front-ends, SerDes interfaces, and DDR controllers has extremely high bandwidth requirements, and sockets must ensure they do not become signal bottlenecks. To achieve this, socket internal terminals employ special curve designs to reduce parasitic inductance, contact areas are optimized to ensure impedance continuity, and some high-frequency sockets even use air dielectric structures to reduce dielectric loss. These details combine to ensure that test results accurately reflect the chip’s performance, rather than being influenced by the socket itself.

In temperature testing, such as high-temperature aging (burn-in) or wide-temperature range behavioral testing, the role of the socket becomes even more prominent. Burn-in tests are typically run above 125°C to expose potential failure points early, and the socket must maintain structural stability, contact pressure stability, and resistance to oxidation at high temperatures. High-quality burn-in sockets use high-temperature resistant metals, ceramic thermal insulation structures, or reinforced plastic materials to ensure compliance under prolonged high temperatures. Substandard sockets can cause uneven pressure or intermittent contact on the chip during testing, rendering the test meaningless.

Furthermore, sockets are also an important tool for engineers during maintenance and after-sales analysis. When market feedback indicates performance issues or malfunctions, manufacturers need to determine the cause through failure analysis (FA). Directly soldered chips are difficult to desolder and easily damage the package, while sockets allow engineers to easily perform repeated verification, retesting under different conditions, or cross-testing of faulty chips, thereby shortening analysis time and improving diagnostic accuracy.

In summary, the role of IC chip sockets in the entire electronic manufacturing and testing system is comprehensive and systematic. From R&D to mass production and post-production verification, the socket plays an irreplaceable role in ensuring reliable chip performance, accurate test results, and efficient manufacturing processes. It can be said that any electronic product relying on high consistency, high speed, and high reliability cannot function without a high-performance socket. It is not merely a connection device, but a crucial node in the manufacturing process ensuring quality and efficiency.

Summary

Although small in size among electronic hardware components, the IC chip socket bears a critical mission across the entire R&D, testing, and mass production process. It determines not only whether the chip can make stable contact and transmit signals accurately, but also the reliability of test results, the improvement of production efficiency, and the consistency of product performance in complex environments. From structural materials to electrical performance, from insertion/removal lifespan to high-temperature tolerance, and the integrity control of high-speed signals, every detail directly affects the quality of the entire product lifecycle. As chip technology continues to evolve towards higher density, higher frequency, and higher power consumption, the technological challenges of sockets will continue to escalate. Innovation in design, materials, and manufacturing will inevitably become a significant driving force for the future electronics industry. Understanding socket selection logic and technology trends can not only help engineers build more reliable systems, but also enable enterprises to maintain a competitive edge in a rapidly changing market.